Matt Fullbrook

Clarkson Centre for Board Effectiveness

March 2015

Click here for a complimentary download of this report →

Acknowledgements

The Clarkson Centre would like to express tremendous gratitude to its Platinum Patrons, without whom this work would be impossible. It is because of the support of Canada’s business community that we are able to continue to explore the effectiveness of boards of directors in new and valuable ways.

Please note that some of the CCBE’s Platinum Patrons have been rated as a part of this study. Please visit the CCBE website for a copy of our Conflict of Interest Statement.

Introduction: Board Ratings and Family Firms

“The directors of such companies being the managers of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners of a private company watch over their own…Negligence and profusion must always prevail…”

- Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776

Background: Canadian Family Firms’ Excellent Performance

After more than 10 years of measuring and rating the effectiveness of the boards of directors of widely held Canadian publicly traded companies, the Clarkson Centre for Board Effectiveness (CCBE) published a report in 2013 about the performance of family-controlled corporations (family firms).Over the 15 year period from 1998 to 2012, Canadian publicly-listed family firms outperformed the rest of the S&P/TSX Composite Index (TSX Index) by a total of 25% return to shareholders. This outcome encouraged the CCBE to reconsider some of its core assumptions about corporate governance.

Adam Smith’s concerns about widely held companies rings true today when considering the loss of approximately $1.2 trillion in shareholder value amongst 25 of the world’s largest banks or the approximately $900 billion in the world’s largest mining companies. All of these companies were widely held and all had boards made up of outstanding individuals, and yet best practices in good governance did not save the day. This is why our study of family firms began with a look at long term shareholder performance. Now we are seeking to understand how that performance was achieved.

The answer might well be that a longer term perspective might be quite literally baked into the family firm DNA.

Board Ratings and the Family Firm Bias

The CCBE’s Board Shareholder Confidence Index (BSCI) is a measurement of a board’s adoption of best practices in board effectiveness and transparent communication. BSCI has had a meaningful and positive impact of Canadian corporate governance, helping to guide behaviour and disclosure in ways that have been useful for boards and meaningful for investors. The scoring metrics that comprise the BSCI are challenging for even the most cutting-edge issuers, but for family firms it is simply not possible to achieve a high rating

Against the 2014 BSCI criteria, a dual class share structure and a few (but not a majority) non-independent directors lose you up to 17 points out of 150 right off the bat: a tie for 50th place. In 2014, the highest ranked family-controlled corporation in the BSCI was Maple Leaf Foods Inc. (MFI), which ranked 46th out of 242 issuers. MFI has adopted structures and practices more similar to a typical widely-held issuer than a typical family firm. For example, the only non-independent director on the MFI board is the CEO and controlling shareholder, Michael McCain. After MFI the next highest ranked family firm was Saputo Inc. in 101st place.

There is a carefully considered rationale behind the BSCI criteria, and also behind the overall sentiment surrounding the current archetype of good governance. An imbalance of shares and votes may seem like an insurmountable obstacle to shareholder democracy. The interests of controlling shareholders may not always be perfectly aligned with those of the other shareholders.

In the case of a family-controlled issuer where the CEO is a member of the controlling family, BSCI treats any directors who have a family relationship to the CEO as non-independent. This makes perfect sense; there is a clear risk that a CEO’s son/sister/husband might make decisions in the interests of family before the interests of the business. On the other hand, those family members have a significant financial and personal interest in the long-term success of the company and certainly have an argument for being at the table.

Currently, the BSCI does not ask whether or not the thresholds for independence (i.e. the percentage of the board that is independent) ought to be the same for family-controlled firms as they are for widely-held corporations. In fact, up until very recently governance researchers have not asked any sort of questions about the extent to which the governance realities of family firms are the same or different from their counterparts. Over the past year, this has changed. Given that Canadian family firms are among the best performers in the country, and also appear to be relatively resistant to major blow-ups, the fact that they consistently rank toward the bottom of the BSCI deserves urgent attention.

The Long View: Canada’s First Family Firm Board Ratings

In 2014, CCBE interviewed directors and executives representing 21 Canadian family-controlled and publicly-listed issuers. The purpose of these conversations was to explore what, if anything, is unique and measurable about the governance of family firms, and to understand what the BSCI gets right and wrong. Does the BSCI miss anything important? Are there criteria that are too strict or too lenient? In the end, the CCBE found enough evidence to support the creation of a new family firm board effectiveness index, which has been named The Long-View. CCBE chose this name because of the clear advantage that family firms have in avoiding the temptations to choose short-term gains over long-term success. The long-term is crucial to a family firm’s survival. This relative immunity to the draw of short-termism is, we believe, a central element of family firm governance, and also a key to their excellent performance over time.

The purpose of The Long View is to measure family firms against criteria that are specifically tailored to their governance realities, and to provide a framework to compare them against each other, rather than against the norms of widely-held issuers.

The process of developing criteria for The Long View began with a philosophical adjustment. Many BSCI criteria reflect generally accepted governance concerns:

- Highly independent boards and committees help to ensure appropriate and impartial oversight of strategy, operations and management, thus helping to avoid late-90s-style disasters (e.g. Enron, WorldCom, Tyco).

- Enhanced disclosure of executive compensation leads to a level of rigour that can withstand external scrutiny, thus mitigating the risk of perverse incentives such as those that contributed to the Global Financial Crisis.

- Majority voting policies provide minority shareholders with greater influence over the composition of the board of directors, who are their key representatives.

However, these and other standards arose from blowups of widely-held corporations, not family firms. Why is it, then, that although we developed governance rating criteria in response to failures by widely-held corporations, family-controlled companies are the ones that are judged most harshly?

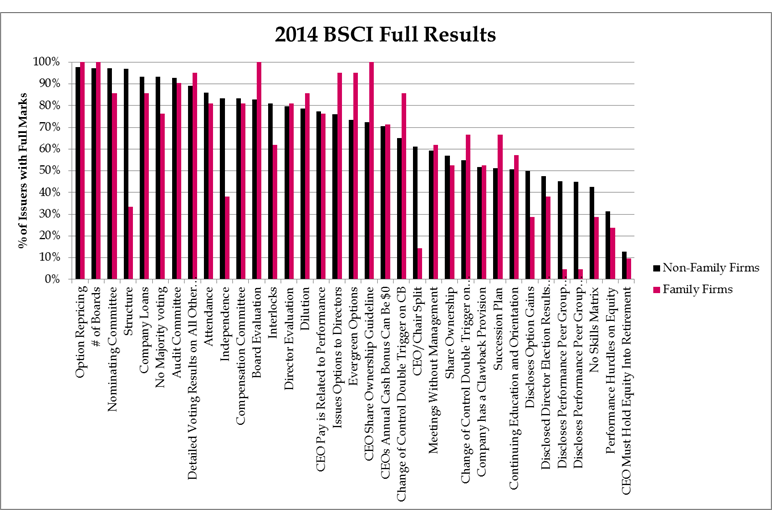

A close look at BSCI outcomes shows that family firms perform at nearly the same level as the rest of the TSX Index on most criteria (See Appendix A). The largest gaps occur in director independence, share structure, CEO/Chair split and compensation peer group disclosure. In each of these areas, family firms perform much worse than the TSX Index. CCBE interviews and research revealed explanations for these gaps, while also suggesting that family firms are achieving effective governance using slightly different yet carefully considered approaches.

The Long-View provides a board ratings framework that addresses the specific nature of family firm governance. We selected 24 criteria against which we scored 37 Canadian publicly-listed family firms. Some criteria from BSCI were included without any adjustment. Others were included, but with slightly different definitions or thresholds. Still more were developed specifically for The Long View. Later in this report, we provide detailed rationale for any new and adjusted criteria. The full Long View methodology can be downloaded from the Clarkson Centre website.

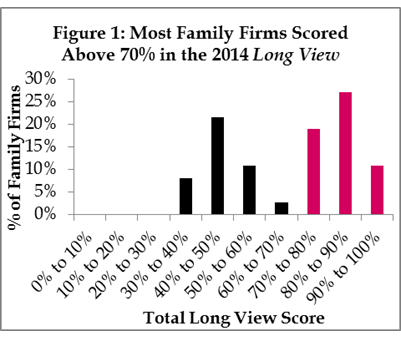

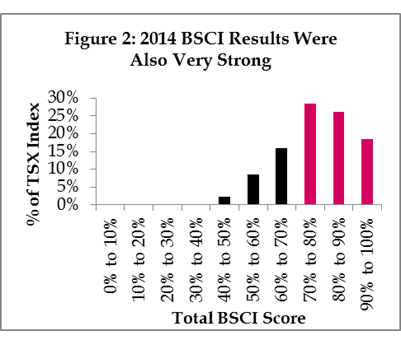

The final results of The 2014 Long View Ratings ended up looking similar in many ways to BSCI result for the entire TSX Index (see Figures 1 and 2). In both cases, a majority of issuers received very high scores (over 70%). The Long View criteria appear not to be too lenient or too oppressive compared to the BSCI. A majority of family firms received credit in most areas, with several important metrics lagging behind (see Appendix B) . Many of these trailing criteria are disclosure-related, rather than behavioural. Transparency to shareholders is an important component of good governance, and one that The Long View can help to influence and improve in ways that are valuable to the public, but not overly onerous to issuers.

Similar to the first year of BSCI, the individual Long Viewscores will not be published this year. This will provide an opportunity to communicate further with family firms to determine what is appropriate for their circumstances, and what can be improved for next year. By looking at the Long View results in aggregate, there is an opportunity to examine whether or not family firms are adopting governance best practices, and highlight areas of strength and potential weakness.

These early results enable the CCBE to re-focus attention on the governance principles that are truly important to family firms instead of applying a one-size-fits-all framework.

For example, in the 2014 Long View ratings, nearly every family firm received full marks for board independence. However, only half received credit for ensuring that independent directors meet without management at every board meeting (a practice that is hugely important according to family firm directors).

The Long View is an attempt to introduce fairness and clarity into the discussion of family firm governance. It will evolve, as the BSCI has, to include new and more nuanced criteria that represent the ever changing landscape of corporate governance. Where many family firms have dismissed the BSCI there is an opportunity for them to embrace The Long View, and to help ensure that it reflects the values and practices that truly matter to Canadian family firms.

The Long View – Full List of Criteria

For full criteria definitions visit the Clarkson Centre website

Percentage of issuers with full marks is provided in parentheses

1. Board Structure

- Question 1: Director Independence (95%)

- Question 2: Audit Committee Independence (89%)

- Question 3: Compensation Committee Independence (78%)

- Question 4: Nominating Committee Independence (73%)

- Question 5: CEO/Chair Split (78%)

- Question 6: Director Interlocks (89%)

- Question 7: Board Skills Matrix Disclosed (30%)

2. Share Ownership

- Question 8: Director Share Ownership Guideline (62%)/p>

- Questin 9a: CEO Share Ownership (97%)

- Question 9b: CEO Share Ownership Guideline (92%)

3. Board Processes

- Question 10a: Board Evaluations (65%)

- Question 10b: Individual Director Evaluations (54%)

- Question 11a: Meetings without Management at Every Board Meeting (51%)

- Question 11b: Policy to Meet without Family Members (70%)

- Question 12a: Formal Succession Plan Process (38%)

- Question 12b: Who is Responsible for Succession Planning? (97%)

- Question 13: Director Retirement Policy Disclosure (43%)

- Question 14: Director Attendance (70%)

5. Disclosure

- Question 15: Description of Director Independence (86%)

- Question 16: Director Bios Disclosed (54%)

- Question 17: Director Ages Disclosed (46%)

- Question 18: Related-Party Transactions (38%)

- Question 19: Detailed Voting Results (78%)

List of Family Firms

For the purposes of The Long View, CCBE defined family firms as public issuers with at least 30% of votes controlled by a family entity. A family entity may be a holding company, an individual or a group of individuals. Ownership must have transitioned to at least a second family generation, or a second generation must be clearly positioned as a successor. In other words, founder-controlled corporations are not included here unless a successor with a family relationship to the founder has been identified and clearly articulated in public documents.>

Our original Long View constituent list included the largest 40 family-controlled issuers on the TSX, however due to changes that occurred over the past year (e.g. takeovers) the list now includes only 37.

|

AGF Management Ltd.*

|

E-L Financial Corporation Limited

|

Newfoundland Capital Corporation Ltd.

|

The Jean Coutu Group (PJC) Inc.*

|

|

Andrew Peller Limited

|

Empire Company Limited*

|

Paramount Resources Ltd.*

|

Thomson Reuters Corporation*

|

|

ATCO Ltd.*

|

George Weston Limited*

|

Power Corporation of Canada*

|

Transcontinental Inc*

|

|

BMTC Group Inc.

|

Guardian Captial Group Limited

|

Quebecor Inc.*

|

Trimac Transportation Ltd

|

|

Bombardier Inc.*

|

Hammond Power Solutions Inc

|

Reitmans (Canada) Limited

|

Vecima Networks Inc

|

|

Canadian Tire Corporation Limited*

|

Linamar Corporation*

|

Rogers Communications Inc.*

|

Velan Inc

|

|

CCL Industries Inc.*

|

Logistec Corporation

|

Saputo Inc.*

|

Wall Financial Corporation

|

|

Clairvest Group Inc.

|

Mainstreet Equity Corp

|

Senvest Capital Inc

|

|

|

Dorel Industries Inc.*

|

Maple Leaf Foods Inc*

|

Shaw Communications Inc*

|

|

|

Dundee Corporation*

|

Melcor Developments Ltd

|

Teck Resources Limited*

|

|

* Indicates S&P/TSX Composite Constituent

NOTE: Public subsidiaries of family firms have been excluded from all analysis. This means that we did not score Canadian Utilities Limited, Great-West Lifeco, IGM Financial Inc., Power Financial Corporation and Loblaw Companies Limited in The Long View.

The Long View: Ratings Methodology

1. Removed Criteria

The CCBE has excluded a large number of criteria from The Long View for varying reasons. In many cases including certain criteria would be a distraction from the core mission to create a board ratings scheme that is truly representative of family firm realities. In other cases, however, the decisions had more detailed reasoning.

Share Structure

The omission of share structure from The Long View will perhaps be the most controversial decision. In some of the CCBE interviews with insiders from single class family firms, there was visceral opposition to the notion of dual class structures. One CEO claimed that dual class structures have been “an unmitigated disaster.” Others were ambivalent, and still others applauded any mechanism that helps to keep control in the hands of innovators, and eyes on the long-term.

CCBE fully acknowledges the potential risk that an imbalance of economic interest and voting control presents to the core of shareholder democracy. We also observed in some cases deep connections between controlling families and minority shareholders.

In the end the CCBE decided that it would be most sensible not to take sides on this topic for the purposes of The Long View. The realities of the impact of dual-class share structures are far too nuanced to be deciphered from public filings. In upcoming years, CCBE will examine this issue further and consider including a question in further iterations of The Long View.

Detailed Description of Family Ownership

The first draft of the Long View rating criteria included a question titled “Detailed Description of Family Ownership”. The full methodology read as follows:

Does the company disclose details about the controlling shareholder’s ownership? A number/percent of shares and votes is not sufficient for credit here. Examples of details that we are looking for include the identity of any family trust or holding company (if such an entity exists) and its beneficiaries, and any explanation of the duties/responsibilities of the trustees and/or beneficiaries. The purpose of the question is to measure the transparency of the ownership structure.

The rationale for including this question is that it is of potential governance value for minority shareholders to understand the structure of the controlling ownership. Are family decisions managed through a family council? Is there a formal ownership succession policy? In reality, however, things are not quite so simple.

Based on the feedback received from family firms, the CCBE decided not to include this question in the final version of The Long View. In many cases, there is simply no detail to provide: the ownership structure really is just “Mr. Smith owns 65% of the Common Shares”. In other cases, the family is unwilling under any circumstances to provide private information about family members beyond what is regulated. One interview participant said that “there is no way I am going to disclose the names of my children to the public just to satisfy your ratings.” CCBE considered this to be a totally reasonable position, and so the decision was made to exclude this question.

Nonetheless, there were 8 family firms who would have received credit under this question and we will examine these in further detail in an upcoming report.

Executive Compensation

For the inaugural edition of The Long View, CCBE excluded all questions pertaining to executive compensation. The overarching rationale for this decision is that the CCBE does not yet have a strong understanding of good compensation governance as it applies to family firms. This is particularly true in the cases where the CEO is a family member. Over the next 2-3 years the CCBE will devote a considerable amount of time to gaining a better understanding of good compensation governance for family firms, focusing particularly on the unique challenge of compensating a CEO who is a member of the controlling family. Most of the governance concerns surrounding executive compensation for widely-held corporations are related to the difficulty in ensuring that the CEO is motivated to behave in ways that are in the best long-term interests of the corporation.

How differently, if at all, do the boards of family firms need to approach this challenge? Should the same tools and mechanisms be used by family firms in order to encourage alignment between the interests of the CEO and the needs of the organization? If not, then CCBE aims to help to build an executive compensation toolkit for the boards of family firms.

In future years, the CCBE will consider the inclusion of executive compensation criteria in The Long View.

2. Adjusted Criteria

Board Independence

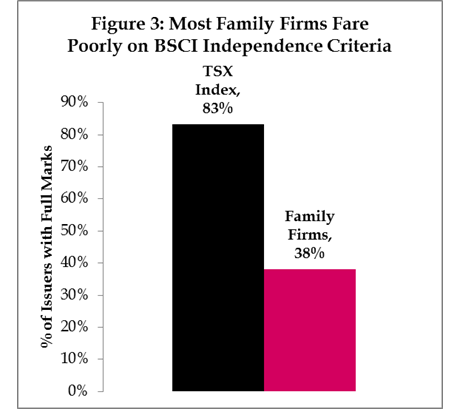

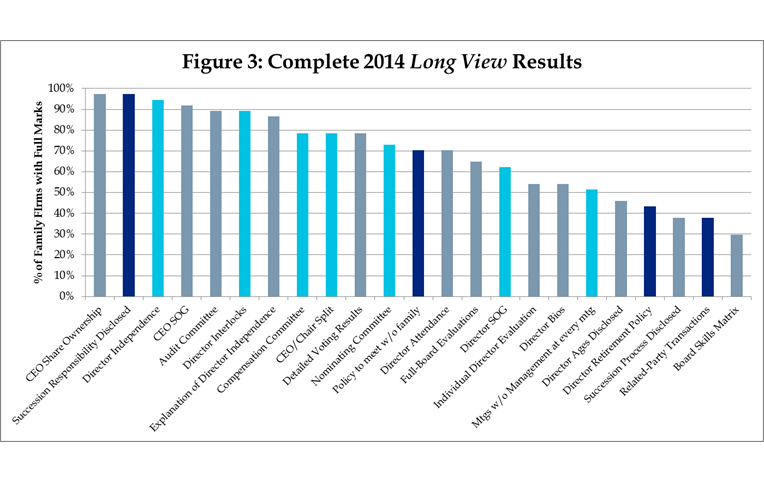

BSCI defines an independent director as being free of any formal relationship to the company or management. The director must not have been an employee of or consultant to the company within the past three years, and in addition may have no kinship ties to employees of the company. If two thirds of the board is independent, then the company receives full marks. According to these criteria in 2014, only one third of all family firms listed on the S&P/TSX Composite Index (TSX Index) received full marks in the BSCI for board independence compared to 84% for the rest of the Index (See Figure 3).

In the CCBE interviews, family firm insiders explained that family representatives on the board add tremendous value. After all, who understands the business better than those who have it “in their DNA”? Usually these representatives are family members, but may also be (paid) trusted advisors or even senior managers of the family’s holding company. Most of these directors get flagged as non-independent by BSCI criteria, thus causing the gap between family firms and widely-held issuers. Nearly half of all widely-held issuers on the TSX Index have only one non-independent director: the CEO.

The CCBE was not, however, inclined to simply relax the independence criteria because the interview participants said it should be so. Although it seems sensible on the surface that an entity which controls 30% or more of a company should be entitled to representation on the board of directors, independent directors are rightfully embraced as an essential component of good governance. The thresholds for board independence in the BSCI, however, were developed with widely-held corporations in mind. Without a controlling shareholder, there would be little excuse for having more than one-third of your board populated by related directors. For the purposes of The Long View, the same definition of independence was kept, but the threshold was adjusted to expect at least half of directors to be fully independent. In addition, the percentage of family representatives on the board may be no more than 10% greater than the percentage of the family’s control. For example, a family that controls 30% of the issuer’s votes may have no more than 40% of the board made up of family representatives, including executives of affiliated companies, whether or not they are independent from management.

The outcome? In The Long View, 95% of family firms received credit for board independence. This may seem high at first glance, but recall that only 3% of widely-held issuers received a full deduction for board independence in the 2014 BSCI. In other words, if we accept that there is value in having family representation on the board of directors of a family firm, then The Long View is no more lenient on family firms than BSCI is on widely-held issuers. In upcoming years, CCBE will consider implementing tiered criteria for independence in The Long View, similar to BSCI.

Committee Independence

Independence criteria for the audit committee were kept unchanged from BSCI methodology, allowing no family members and no non-independent board members. CCBE made slight adjustments to the criteria for the compensation and nominating committees, in order to allow a certain amount of family representation. The research revealed that family firm board committees often benefit from a balance of points of view, including that of the controlling family.

At the moment the criteria allow up to 50% of the compensation committee to be made up of family members, as long as they are independent from management. This means that if the CEO is a family member, then appointing another family member to the compensation committee – which determines the CEO’s compensation – will result in a deduction. Up to 50% of the compensation committee may be made up of executives from a parent company.

Similarly, we allowed up to 50% of the nominating committee to be made up of family members, as long as they are independent from management. We additionally allowed one non-independent director to sit on the nominating committee, regardless of his or her relationship.

A majority of the family firms that received deductions for committee independence in The Long View are not constituents of the TSX Index, and as such have not been subject to the tremendous scrutiny of the BSCI as well as the Globe & Mail’s Board Games, and other media and regulatory sources. As a result, even with slightly more flexible criteria, the overall results from The Long View are not as good as the 2014 BSCI. This is especially clear in the case of the nominating committee, where 86% of family firms received full marks in the BSCI, and only 73% received full credit in The Long View. It is the CCBE’s hope that The Long View might encourage additional family issuers to consider the benefits of increased committee independence.

CEO/Chair Split

The trend of splitting the roles of the CEO and Chair has proliferated across Canada over the past 20 years, becoming the norm among large publicly-listed corporations. In a 2014 interview, CCBE Conway Chair David R. Beatty explained that “the same person can’t do both [the job of the CEO and the job of the Chair]; it’s difficult for the fox to overlook the henhouse.”[2] More

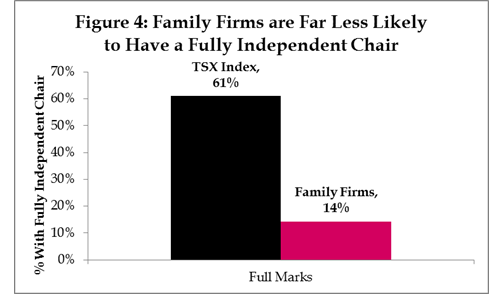

than 60% of the TSX Index received full marks in the 2014 BSCI for having a fully independent Chair. Family firms, however, fared much worse against these criteria (See Figure 4). Only one family firm, however, received a full deduction in this area, which means that the CEO and Chair positions are combined, and that the board has not appointed an independent Lead Director to ensure the independence of the board.

Approximately 65% of family firms have either chosen not to split the CEO and Chair roles or have appointed a non-independent family member to serve as the Chair of the board (See Figure 5).

The interviews with family firms revealed that, this is because they believe that a family member, as a representative of the controlling entity, is best positioned to guide the board in its strategic decision making. Although they are less likely to split the role of the CEO and the Chair, family firms are deeply concerned about the inherent conflict of interest that this structure presents. As a result, most family firms with related Chairs have appointed independent Lead Directors, and have empowered them to fully monitor and ensure the independent operation of the board of directors (See Figure 6).

Because of the unique value of family members in the Chair role, The Long View gives full credit to boards that have split the CEO and Chair roles with an independent Chair, or in any case where a fully independent Lead Director has been appointed. This provides flexibility for a non-independent family member to be Chair as long as an independent Lead Director is in place. 80% of family firms received credit for CEO/Chair Split in the 2014 Long View ratings.

Director Interlocks

Both BSCI and The Long View define a director interlock as an instance where two directors sit on two different public boards together. Similarly, both ratings allow no more than one director interlock in order to get full marks. For the purpose of The Long View, however, there are not any limits on interlocks between affiliated public issuers. For example, if two directors sit on the board of a family firm as well as the board of its publicly-listed subsidiary, this will not count against their Long View rating. As a result, only those issuers that have more than one director interlock with non-affiliated corporations received deduction in The Long View. Three family firms received deductions in The Long View, compared to eight in BSCI.

In the interviews, family firm board members explained that it is often of great benefit for them to have a small number of directors who sit on multiple affiliated boards. This arrangement helps to ensure that the strategic and financial interests of each entity are suitably aligned. It also enables a more efficient flow of information throughout the group of companies. As opposed to interlocks between widely-held corporations, which can present the risk of decisions being made in the interests of an entirely separate entity, interlocks within a family firm’s larger corporate structure can present a governance benefit.

Director Share Ownership Guideline

It is generally accepted that a certain amount of share ownership by independent directors helps to align their interests with those of shareholders, thus resulting in beneficial decision-making. The Canadian Coalition for Good Governance’s Policy on Director Compensation states that “Directors should ideally acquire an equity stake in the company upon joining the board and add to that stake over time.” [3] According to BSCI criteria, an issuer gets credit for having a director share ownership guideline (Director SOG) if the board requires each director to own at least three times the dollar value of their annual director retainer in shares and/or deferred share units.

In the case of some family-controlled companies, the expectation for directors to own a significant stake is somewhat more complicated. The CCBE believes that director share ownership is an effective means to align the interests of directors with those of other shareholders. In order to acknowledge the different situations of different family issuers, The Long View gives credit to issuers that have a Director SOG in place regardless of the amount.

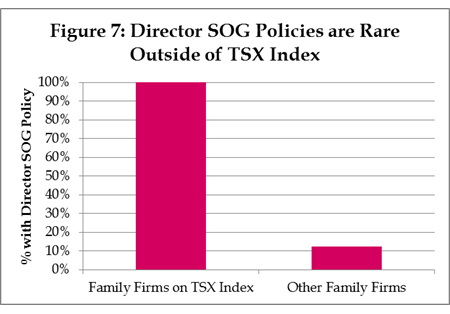

Every single family firm on the TSX Index received full marks in The Long View for this category. However, of the family firms not listed on the TSX Index, only two have any kind of Director SOG in place (See Figure 7). This suggests that the adoption of a formal Director SOG may often be in response to external pressures such as BSCI and the Globe & Mail’s Board Games, both of which have expectations pertaining to director share ownership.

Meetings without Management at Every Board Meeting

Allowing directors to meet without management is a simple, yet highly effective governance mechanism. In fact, according to many of the interview participants, this may be the single most important practice to ensure that family firm boards make effective and independent decisions. The BSCI criteria have been left largely untouched. However, BSCI only gives full marks if the board meets without management at every single board meeting, regardless of its agenda. For The Long View, credit was given to boards as long as independent directors meet without management at every full board meeting. If the board holds a strictly transactional meeting – to simply approve a single item that has already been discussed, for example – then we do not expect the board to hold an in camera session. Half of the boards studied for The Long View received credit in this category.

Because of the emphasis that family firms put on the value of in camera sessions in the interviews, this area as one of the most important opportunities for improvement by family firms. A simple adjustment to each board meeting agenda to allow independent directors to meet without management will help to ensure that board decisions are truly independent. In some cases, a company may not have received credit in The Long View simply because of unclear or inadequate disclosure. In these cases, a small improvement to disclosure can have a significant impact on shareholder confidence.

3. New Criteria

Policy to Allow Independent Directors to Meet without Family Members

This category asks whether or not the board has a formal policy that allows independent board members to meet not just without management, but without family members as well. Several of the interviews with independent directors revealed that family members can often have a disproportionate influence on independent board decisions. In many cases this is appropriate, and independent board members find the family’s perspective to be invaluable from both strategic and operational points of view. However, independent board members sometimes need to hold truly independent discussions, free from the influence of any specific group.

For the purposes of The Long View the CCBE does not expect the policy to have formal requirements regarding the frequency, duration or structure of these meetings. In addition, any family firm with a CEO who is a family member received credit here by default if the board has a policy to meet at every meeting with only independent directors. 70% of family firms received credit for this question in the 2014 Long View ratings.

Board Process to Ensure the Appropriateness of Related-Party Transactions

Many large family firms are part of a network of affiliated companies in related, or identical, industries. A publicly-traded family firm, however, must ensure that any transactions with its affiliates are undertaken under fair and appropriate terms and conditions. The CCBE interviews with family firm board members revealed that this is a crucial role for the board of directors, and that independent board members must be thorough in their examination of any related-party transactions.

CCBE gave credit if a board disclosed a formal process for monitoring the fairness of related-party transactions, or if the company clearly stated that no such transactions take place. Only 40% of family firms received credit for this question in the 2014 Long View ratings.

Director Retirement Policy, Director Ages, Director Bios

These three criteria were inspired by the Globe & Mail’s Board Games report. Many of the interviews with family firm board members revealed that it is crucial for independent board members to have formal processes to monitor and optimize the skills and composition of the board. In addition to creating and maintaining a formal board skills matrix, the disclosure of basic information to the public gives investors an opportunity to scrutinize the makeup of the board and the characteristics of each board member. Even if minority shareholders do not have enough control to influence director elections, the board is still accountable to them, as well as to the controlling family and other stakeholders.

Next Steps

CCBE has learned a great deal through the process of compiling The Long View. The research has opened up dialogue with many influential families, corporations and researchers. It has additionally broadened the understanding of the governance challenges that are unique to family firms. After all feedback on this report has been received, the CCBE will continue to explore family firm governance in Canada and beyond. The primary goal is to understand what good family firm governance looks like: what are the questions that family firm boards should be asking, and what questions should the CCBE, investors and the public be asking them? Over the course of the next 3 or 4 years, the hope is for family firms to no longer be pariahs when the conversation turns to corporate governance or board effectiveness. Rather, the goal is to incorporate the lessons from these organizations into the broader discussion of corporate governance for the benefit of all businesses.

Appendix A: Full 2014 BSCI Results

Appendix B: The Long View 2014 Full Results

Grey = Unchanged CriteriaLight Blue = Adjusted CriteriaDark Blue = New Criteria

[1] Fullbrook, M., & Beatty, D. R. (2013, Fall). The Upside of Family Ties. Rotman Management, pp. 59-63.

[2] Bailey, J. & Koller, T. (2014, Autumn). Are you getting all you can from your board of directors?. McKinsey on Finance, pp. 18-22.

[3] Canadian Coalition for Good Governance, CCGG Policy Director Compensation, February 2011