Along with McKinsey’s Dominic Barton, you have been closely involved in the quest to focus investors' mindsets on the long term. Describe how and why you became involved.

It all started with an article Dominic wrote for Harvard Business Review [“Capitalism for the Long-Term”] back in 2011. In it, he argued that, if we didn’t shift to more long-term thinking — and start producing greater prosperity for citizens — capitalism could be at risk as an organizing principle for society. Dominic made this point extremely well in the article, but because he’s a good friend of mine, I called him up and said, ‘Dom, you’re being a typical consultant — pointing out all these issues, but not doing anything to find solutions. What are you going to do about it?’ He came right back at me — as he is apt to do — and said, “The question is, Mark, what are we going to do about it?’ That’s how our Focusing Capital on the Long-Term initiative started out.

‘FCLT’, as it is now known, recently became an official organization. Tell us more about it.

The founding partners include BlackRock, Mackenzie, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) and corporations including Dow and the Tata Group. Others, like GIC, Unilever and BP joined shortly thereafter. Together, we are working to create meaningful reform — not just sitting around talking about the problem. I like to think of FCLT as a do tank, not a think tank.

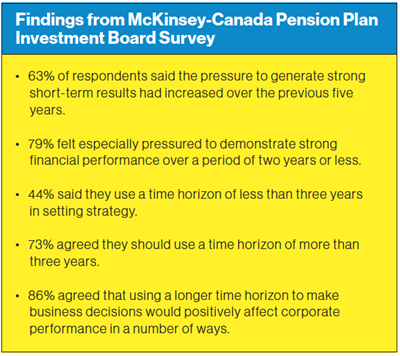

The main source of the problem, we believe, is the continuing pressure on public companies to maximize short-term results. We’re really trying to change the way markets operate, so we can be in a position to create greater long-term value for shareholders and ultimately, for the owners of assets, which are individual

savers around the world. If we can achieve that, we believe it will create a greater degree of prosperity for everyone.

Are we willing to make the hard decisions and trade-offs that a long-term perspective demands? I don’t think we’re seeing evidence of that yet.

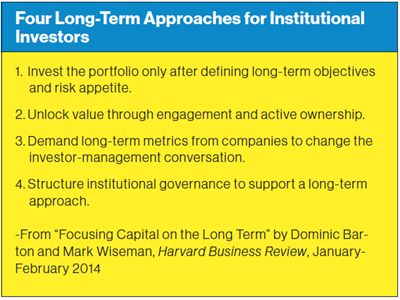

We also believe that the single most effective way to move forward is to change the strategies of the biggest investors out there. They include asset owners and managers like pension funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds and insurance firms, all of whom invest on behalf of long-term savers. Today, they own 73 per cent of the top 1,000 companies in the U.S. That is a huge increase over the 47 per cent they owned in 1973. The good news is, these players have both the scale and the time horizon to focus their capital on the long term.

We also believe that the single most effective way to move forward is to change the strategies of the biggest investors out there. They include asset owners and managers like pension funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds and insurance firms, all of whom invest on behalf of long-term savers. Today, they own 73 per cent of the top 1,000 companies in the U.S. That is a huge increase over the 47 per cent they owned in 1973. The good news is, these players have both the scale and the time horizon to focus their capital on the long term.

You have noted that, eight years after the global financial crisis, we have yet to see meaningful reforms in this arena. Talk a bit about the progress made to date.

This issue has gotten a lot of traction in business circles, as well as in political and regulatory circles — so I do think it has entered into the consciousness of business people on a global basis. As to whether or not we are willing to make the hard decisions and trade-offs that a long-term perspective demands — I don’t think we’re seeing evidence of that yet. There is still a tremendous amount of short-termism in public markets: public companies continue to manage to quarterly earnings cycles, and investors continue to be relatively short-term in the way they measure and reward performance.

So, although we’ve helped to raise consciousness about the issue, there is still plenty of work to be done in terms of getting people away from short-term thinking. The challenge is, this involves doing something that is extremely difficult: changing human (and corporate) behaviour. That includes changing the way boards operate, changing the way asset owners and managers operate, and changing some of the regulatory structures that we have in place. It’s going to require a long-term effort—but I do believe we can make a meaningful impact.

Shifting to a longer-term mindset will mean changing many of the traditional ways companies have been governed. What are some of the key elements of this?

A number of things have to change in corporations. One thing we are focusing on at FCLT is, ‘What is the role of the Board?’ All of this begins with having the right people on your board, and having them focus on the right things. Today’s boards spend far too much time looking in the rear-view mirror — doing things like

reviewing financial statements. But that only tells you what happened in the past: it is not going to help you with the future.

We need board members who are engaged in ensuring that management has a long-term strategy in place, and who encourage management not to focus on things like quarterly earnings. But if we expect board members to be proactive in creating longterm shareholder value, they have to be properly incented. It might seem counter-intuitive, but we actually believe that board members should be paid more, because they need to be more engaged and financially aligned with a firm’s long-term outcomes.

We strongly recommend that companies stop giving quarterly guidance, because we don’t see it as being particularly useful. But one should not confuse that with the need for ongoing transparency, generally. Boards need to demand and then report on the long-term metrics that are relevant to their company.

What role does shareholder activism play in all of this?

People hear about a shareholder activist forcing a board to pay out more dividends, or to break up a company, and they say, ‘These activists are pushing companies to be more short-term.’ But my view is that activists aren’t the real issue here. I actually believe that — as in any other occupation — there are good activists and bad activists. Some of them truly want to make value-creating changes, while others are only in it for short-term gains.

By and large, activists are a symptom rather than a cause of short-term thinking and behaviour. If companies and investors undertook some of the measures that we have suggested [see sidebar] to get longer-term thinking into their investment value chain, there would be less room for activists to have influence. The fact is, shareholders have to start acting like owners. Here’s a simple example: an activist buys two or three per cent of a public company’s shares, and soon after, starts to put all kinds of demands on the company. My question is, where are the other 97 or 98 per cent of the owners of that company? Why aren’t they speaking up to protect their own long-term interests?

By and large, activists are a symptom rather than a cause of short-term thinking and behaviour. If companies and investors undertook some of the measures that we have suggested [see sidebar] to get longer-term thinking into their investment value chain, there would be less room for activists to have influence. The fact is, shareholders have to start acting like owners. Here’s a simple example: an activist buys two or three per cent of a public company’s shares, and soon after, starts to put all kinds of demands on the company. My question is, where are the other 97 or 98 per cent of the owners of that company? Why aren’t they speaking up to protect their own long-term interests?

Rather than blaming activists, we should instead blame some of these companies for not being clear enough about the long-term strategic outcomes they are trying to achieve, and for not having metrics in place to measure those things. I also blame the institutional-investment community and the asset-management community, who quite frankly aren’t acting like owners, and are allowing someone with two or three per cent of a company’s stock to have disproportionate influence. They are partly responsible for the rise of shareholder activism.

Like anything else in life, sometimes activists are right and sometimes they’re wrong. If you look at Pershing Square Capital Management’s involvement in the Canadian Pacific Railway situation, I think most observers would agree that they had a point — and certainly, CP’s subsequent performance confirms that; but that same group has been involved in other situations where it’s difficult to argue that they created any long-term value. I really think we’re spending too much time thinking that activists are the problem. The root causes of this issue are short-term behaviour by boards, and investors failing to act like owners.

It has been said that up to 80 per cent of the market value of the modern corporation lies in intangible assets. If this is the case, what needs to change in terms of financial reporting?

I think it very much depends on the company. I’m sure there are some companies where 100 per cent of the value rests in intangible assets; and there are others that are more traditional in terms of owning tangible assets — like real estate, for example. At the end of the day, I don’t think changing financial reporting standards is as important as figuring out how to value something like ‘goodwill’, for example. To me, as an investor, what is most critical is having complete transparency of information, so that I can understand the intangible aspects of a company’s enterprise value. Investors should never value a company based solely on the shareholders’ equity showing up on the balance sheet. At the end of the day, you have to value a company based on its ability to generate cash in the long run — and cash can be generated by both tangible and intangible assets.

It’s not just about intangible assets — it’s also about the other side of the equation, which is liabilities. Take something like litigation risk or climate risk. Companies need to do a much better job of disclosing their long-term risks, and things that may affect their sustainability — from environmental impact to labour practices to supply chain management. If we had better disclosure around these sorts of things, it would allow investors to be more accurate in valuing a company.

The work that Bob Eccles and others have done on creating ‘sustainable accounting standards’ may be a bit too prescriptive, but I believe there is something to it. The idea of a greater degree of transparency and better reporting by companies — not just around traditional metrics — is very important, going forward. For example, the Carbon Disclosure Project has been quite successful in enabling investors to make better decisions.

At CPPIB, a ‘quarter’ meant 25 years, not 90 days. That is probably pretty close to a general definition of 'long term'.

It has been said that as an initial step, all parties involved need to agree on the definition of ‘long term’. How do you define it?

That’s a really good question, because there are a lot of different definitions out there. I think it’s interesting to look at Canada’s Indigenous peoples’ definition: the Iroquois Nation has this concept of ‘seven generations’, whereby whenever they made a decision, the elders had to be thinking about the impact that it would have seven generations down the line. There are similar philosophies in Chinese culture. I’m not suggesting that our corporations need to be thinking seven generations ahead of time — and again, it’s somewhat dependent on the business. I don’t think you can necessarily measure it in every context in the same way — so it’s okay for different companies to think about it differently.

Of course, if your business activities impact the environment, you have to think about your environmental practices over a much longer term. In that case, it might actually be seven generations. But in terms of your technology strategy, if you always thought seven generations ahead, you couldn’t progress. So, there is no single definition of ‘long-term’; but by and large, it’s probably close to the approach I used at the CPPIB: I always said that for CPPIB, a ‘quarter’ meant 25 years, not 90 days. That is probably pretty close to a general definition of long term.

For example, if you look at the decision of some major companies to move into China —

Volkswagen,

Procter & Gamble,

Walmart,

Starbucks — in each case, those decisions did not pay off for over a decade. Each company experienced a long period of investment and losses; but if they had not made those decisions, I would argue that their entire business model might now be in peril — given how important the Chinese market is, and will be, going forward. In each case, they were thinking at least a decade or more out, and the benefits of being early movers are still paying off — and will continue to do so.

It is critical for each and every corporation to define what it means by long-term. Then, set a long-term strategy, define a set of metrics, and report on their success. Of course, you can't just ‘set it and forget it’. It’s not like you’re going to have the same long-term strategy for the next 25 years; if something isn’t working, you have to adjust it. Also, just because you have a long-term strategy, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t pay any attention to the short-term. It’s about keeping your investment eye fixed on the horizon rather than staring down at the cracks in the sidewalk in front of you.

You recently embarked on a new phase in your career at BlackRock, the world’s largest investment company. What do you foresee as your greatest challenge ahead?

Clearly, BlackRock’s business is very different from what I was doing at CPPIB, so I’ve got a lot to learn. For example, CPPIB had the rarefied position of not having to raise capital: it came to us through the operation of Canada’s national pension plan. But at BlackRock, everyone — including me — has to get out there and prove themselves, each and every day. It’s also a much larger organization, both in terms of its assets under management and its employee base. I’m very excited to learn all about it.

That has actually been a constant throughout my career: whether I was practicing law, working at the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan or at CPPIB, I have always made it a habit to learn something new every single day. I plan to continue to do that.

Click here for a PDF version of this article.

Mark Wiseman (Rotman MBA ’96) is the Global Head of Active Equities for BlackRock and Chairman of BlackRock Alternative Investors. He also serves as Chairman of the firm’s Global Investment Committee and on its Global Executive Committee. He joined BlackRock in 2016 from the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, where he served as President and CEO since 2012. Mark is a member of the Advisory Council on Economic Growth, which advises the Canadian Finance Minister on policies to achieve long-term, sustainable growth. He is also the Chairman of the Focusing Capital on the Long Term initiative, which he co-founded, serves on the boards of several non-profit organizations and is a certified member of the Canadian Institute of Corporate Directors.

This article originally appeared in 'Smart Power' (Winter 2017).

Subscribe today to get the full Rotman Management experience - and never miss an issue!