As each day passes, more and more of our choices and behaviours are occurring online. We work, shop and communicate with the help of platforms like Amazon, Twitter and Zoom. Even daily behaviours such as sleeping, eating and exercising are performed with our constant companions by our sides — smartphones, wearables and smart-home devices. Most of these devices are powered by algorithms and recommendation systems that are designed to automate and augment our choices. And as a result, the digital world is rapidly transforming human behaviour as we know it.

Technologies that simplify consumer choice — for example, providing the ability to quickly search for products and recommendations — have bumped the concept of ‘choice architecture’ to the top of the agenda for many organizations. Choice architecture can be defined as ‘the design of different ways that a choice can be presented to decision-makers, and the impact of that presentation on their decision-making.’ A simple example is donor cards: Research shows that if the user is required to opt-in to become a donor, take-up rates are low; but if people are automatically signed on unless they opt-out (i.e. the default changes), take-up rates increase.

The current landscape of information technologies has significantly changed the myriad of choice architecture we face daily. The result: Choice architecture is both more digital and more intelligent than ever. And wherever there is choice architecture, there will be nudging.

Online nudging practices are constantly being evaluated and

adjusted, making them increasingly effective over time.

The Realm of the Digital Nudge

A nudge can be defined as ‘any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without removing access to other options or significantly changing economic incentives.’ To count as a nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. For example, social media platforms such as Facebook design choice architecture to encourage user engagement by curating information based on observed user preferences and past behaviour; online retailers such as Amazon nudge users to buy more by scaling up traditional choice architecture with the help of personalized recommendations; and smartphone devices and applications themselves — on which people spend hours a day — are designed precisely to reinforce mindless consumption and habitual checking. These and other online nudging practices are being rapidly evaluated and adjusted with the help of online experiments in the form of thousands of A/B field tests — making them increasingly effective over time.

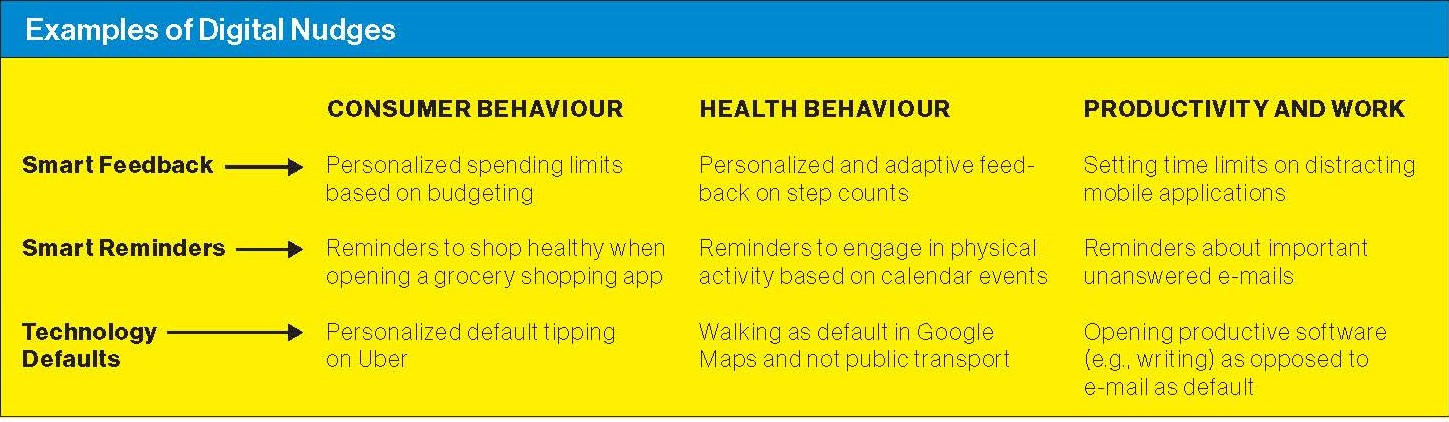

As indicated, digital nudging applies the idea of choice architecture to a digital environment by passively changing user interfaces to guide choices. And it augments proven-to-be-effective behavioural nudges (e.g. feedback, reminders, planning prompts) by designing and implementing them in novel technologies such as apps and wearable devices. Digital nudging ultimately allows designers to select the ‘right’ nudge at the right time, for the right individual, by learning to adapt to that individual’s preferences and context. Two key principles of digital nudges are:

DESIGN IS IMPORTANT. Research in human-computer interaction (HCI) has extensively explored how to design technologies to be persuasive and support behaviour change, allowing for the emergence of common principles for good design, including self-monitoring, simplification, personalization and rewards.

DATA IS ALSO IMPORTANT. The recommendation systems on Google, Amazon and Netflix are prime examples of AI technologies that simplify and guide choice by learning about user preferences from data on their past choices. Current and future advancements in machine learning and AI will allow digital nudging applications to be even more effective and precise.

The Tools of Choice Architecture

Defaults are one of the most powerful tools of choice architecture — and digital technology is full of them, ranging from security and privacy settings on your devices to tipping defaults on Uber and product rankings on Amazon. Defaults are most useful to individuals when they fit their preferences. For example, after an Uber ride, nearly 60 per cent of people never tip, and only one per cent always tip. This observation warrants personalizing the default option so riders don’t need to make an active choice after every ride. Beyond personalization at the individual level, the characteristics of a specific ride could also be used to tailor the tipping suggestion for every ride (e.g. ‘late arrival equals less tip’).

Almost every active nudge can be augmented with technology and data. Reminders can be personalized to an individual and optimized using timing; and feedback can be increasingly smart. A famous example is the fixed criterion of 10,000 steps a day, which serves as an imperfect reference point for optimal behaviour. Digital nudging allows for the design of personalized and adaptive goals based on an individual’s baseline, their ability to achieve the goal and their previous response to feedback.

Following are three domains where digital nudging can be the most powerful:

CONSUMER CHOICES. Digital technologies have transformed the choice architecture of everyday consumer decisions. Organizations use digital tools to personalize user interfaces and deploy recommendation systems to enhance engagement, influence choice and increase revenue. Digital nudging tools can also be just as effectively targeted to help consumers choose products, services and activities that maximize their own preference and utility (i.e. products that are healthy, sustainable and cost-effective.)

Changing the underlying choice architecture is the standard approach to influencing consumer choice. For example, a search ranking of products can focus on nutrition for Consumer A, and cost for Consumer B. Another approach is to provide the consumer with tools to change the choice architecture in support of their preferences. For example, recommendations can be designed to be more user-centric by introducing ‘preference-elicitation mechanisms’ for users, which entail a short survey completed by the user. A third approach is to design third-party digital nudging applications that augment consumer choices across platforms, such as automatically providing price comparisons between online retail stores. The opportunities and design choices in digital consumer environments are unlimited.

HEALTHIER BEHAVIOUR. Changing one’s behaviour to sustain health is considered one of the most important challenges in the world today. Mobile technologies are often proposed as being part of the solution, as evidenced by the proliferation of mobile apps designed to help people become more physically active, eat healthier, stop smoking and drinking, and reduce stress. While health apps and devices are full of digital nudges, most have not been systematically tested in controlled settings. For instance, who says 10,000 steps per day should be everyone’s goal? To drive change, it is necessary to leverage emerging health technologies while accounting for basic elements of human behaviour and ever-developing findings in the science of health-related behaviour.

To date, research has targeted the nudging of daily health behaviours such as medication adherence, physical activity and smoking. Reminders can be tailored and optimized with information about a user’s past behaviour and current context. Nudging can also be designed to drive engagement and reduce attrition with evidence-based clinical products — a major challenge of current health technology. Moreover, the role of data and machine learning is rapidly growing to realize the vision of personalized precision-health technology.

PRODUCTIVITY AT WORK. Few would argue that the future of work will rely on digital technology. Work technologies like Zoom for videoconferencing and Slack for communication are now familiar to most of us, but they could be redesigned to support goals such as increased productivity and reduced stress. And digital nudging tools can support these goals in the flow of daily work. Simple productivity advice can also be supported with digital nudging. For example, research indicates that individuals should start working on their most important projects at the beginning of the workday, rather than checking their e-mails first. Here, the gap between intention and behaviour can be mitigated with reminders and planning prompts. Digital nudging tools could support this behaviour even further by:

• Delivering reminders at the start of the workday based on location data;

• Defaulting operating systems to open the software with the most important project first; and

• Providing rewarding feedback when an individual follows through, and reminders when they do not.

One of the more novel and interesting applications of digital nudging involves the use of technology itself. Armed with the tools of Behavioural Science, choice architects are often responsible for creating engaging, addictive and distracting digital technologies ranging from smartphones to social media websites. Digital nudging can help individuals self-regulate and tackle their own habitual and mindless use of technology. Examples of such digital nudges include changing the colour of the screen to be less engaging and creating personalized and adaptive goals for distracting social media apps.

Designing Digital Nudges

Based on a synthesis of current research and the affordances of technology, I propose three guidelines for the design of digital nudging solutions. All three can apply to the digitization of existing nudging practices as well as to the development of novel applications.

PRINCIPLE 1: EMBRACE TECHNOLOGY

Designers of digital nudges should choose a technology for their nudge based on its proximity to the targeted behaviour and the unique features of the technology. For example,

• Online shopping websites allow designers to easily track and nudge behaviour at the point of purchase using choice architecture tools;

• Smartphones are both personal and ubiquitous and allow one to design and deliver a large set of digital nudges via mobile apps; and

• Wearables allow for the collection of novel data (e.g. heart rate) and nudge individuals with novel feedback (i.e. haptic feedback).

PRINCIPLE 2: PUT DATA TO WORK

Designers of digital nudges should identify the necessary data to track behaviour and other contextual variables to optimize nudging techniques. For example,

• Reminders can be delivered to anyone via text message, but tailoring reminders with data about location requires mobile devices and applications;

• Planning prompts will be more effective when tailored with data from calendar events about other activities of daily life; and

• Adaptive feedback on physical activity requires sensors equipped to capture these activities, for example, in mobile phones or wearables.

PRINCIPLE 3: EXPERIMENT

Designers of digital nudges should leverage digital experimentation to rapidly optimize nudges and choice architecture. Digital experimentation should allow for the following:

• The evaluation of a large set of possible nudges;

• Personalization of nudges based on individual preferences and adaptation to the changing contexts of daily life; and

• Deploying and evaluating the effects of digital nudges continuously.

In closing

Nudges in the realm of digital technology are not a panacea for influencing and improving human behaviour. For some choice settings, choice architecture and nudges can remain offline as they would not benefit from personalization. For others, technology might add unnecessary complexity and limit scalability. The science of digital nudging is still nascent and warrants some caution before it is applied ubiquitously to every choice environment. And importantly, the digital divide remains very real. Not everyone can benefit from digital technology equally, and designers must be aware of this as consumer choices continue to shift to the digital realm.

Michael Sobolev is a Project Scientist at the Cancer Research Center for Health Equity at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. He holds a PhD in Behavioural Science from the Technion Israeli Institute of Technology and an MSc in Business and Organizational Behaviour from Tel Aviv University. This article has been adapted from his chapter in Behavioural Science in the Wild (Rotman-UTP Publishing, 2022), co-edited by the Rotman School’s Canada Research Chair in Behavioural Science and Economics, Dilip Soman.

A Laboratory of Behavioural Interventions

by Nicola Lacetera and Mario Macis

|

|

Blood transfusions allow medical professionals to address a wide variety of emergencies, from trauma-induced blood loss to blood replacement during surgeries. Population aging and the increase in surgical procedures such as organ transplants are further increasing the demand for blood. The question is, What will influence human behaviour more: appealing to altruistic motives to the request or providing an economic incentive? We decided to find out.

Interventions targeting altruistic motives. According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization, the objective of national blood procurement and allocation systems is “to obtain all blood supplies from voluntary non-remunerated donors.” There are several ethical and behavioural foundations at the origin of this stance. The first is a strong reliance on the power of altruism as a motivator: People might want to help others because of a genuine desire to increase the other’s wellbeing, even at the expense of their own. In his 1759 book The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith claims that this “virtue of beneficence” derives from natural human sympathy. Behavioural scientists call this tendency ‘warm glow’ or ‘impure altruism.’ Another strong underlying source of altruistic behaviour is the desire to signal to others — or to oneself — that one is ‘a good person,’ and to improve one’s reputation in a community. Yet another source of altruism derives from reciprocal feelings, whereby a person behaves altruistically with the expectation that the recipient will reciprocate in the future, should the need arise.

Interventions applying economic incentives. The second key behavioural claim at the root of promoting purely altruistic donations is that material rewards or compensation might actually have perverse effects that do not correspond with the ‘rational agent’ view. According to this view, the higher the reward for an activity, the more an individual will make an effort in that task. In his 1970 book The Gift Relationship, British scholar Richard Titmuss claimed that material rewards might change a donor’s perception of the nature of their act from being altruistic to resembling a market exchange. This could reduce altruistic drive without a counterbalancing increase in material incentives — especially if the amount of the reward is small. Titmuss also argued that monetary incentives would attract donors with a higher risk of carrying infectious diseases. According to Titmuss’s hypothesis, rewards are especially appealing to low-income individuals who are, in turn, more likely to be affected by blood-transmissible diseases due to unhealthy lifestyles and risky behaviours.

The strong objections to providing any form of compensation to blood donors derive from multiple concerns. At the same time, both in the Western world and even more so in low-and-middle-income countries, guaranteeing the availability of blood for transfusions is critical and has proven difficult. The seasonality of the blood supply compared to the constant need, moreover, adds to the difficulty of keeping an adequate inventory level. Even in contexts where the organization of procurement and allocation is advanced, relying on altruism is often insufficient to cover the demand for blood.

This conundrum has stimulated efforts to devise incentive programs that would minimize potential ‘crowding out’ effects as well as addressing ethical concerns. In Italy, for example, employees have the right to a paid day-off work on the day they donate. In our own research we investigated the effectiveness of this policy and found that those who benefit from it do indeed donate blood more frequently. This implicit economic incentive, however, is expensive: We estimated that each additional unit of blood collected due to the ‘day-off incentive’ would cost about 400 Euros.

In the U.S., American Red Cross (ARC) blood drives sometimes offer rewards such as T-shirts and gift cards to people who donate. In research we did in collaboration with the ARC, we found that these rewards did increase donations, with rewards of higher economic value resulting in more additional donations than rewards of smaller value. However, we also found that part of the increase in donations at blood drives offering rewards came from a reduction in turnout at neighbouring blood drives that were not offering incentives. On the one hand, our findings highlight the importance of carefully distributing rewards across geographic areas to avoid competition between blood drives, and on the other, they imply that the use of rewards in periods with lower seasonal supply can be effective.

Our research indicates that even small economic rewards can increase donations in a cost-effective way. For example, the cost of one extra unit of blood collected using a $5 gift card as an incentive was $22. In recent years, the ARC has offered gift cards during periods of low supply — for example, in the winter. In an intervention conducted in collaboration with an Argentine blood bank, we found again that gift cards motivated additional donations, whereas ‘social-image stimuli’ (e.g. T-shirts with designs indicating the wearer was a blood donor) were not as effective.

Overall, the evidence demonstrates that certain economic incentives have positive consequences in terms of the quantity of blood collected. People respond in a rather standard way: higher-value rewards have bigger effects than lower-value rewards — even in the case of an archetypically altruistic activity like blood donation. The fact that several organizations allow and make broad use of (appropriately framed) economic incentive programs suggests that there are further opportunities out there to leverage motives beyond altruism — so long as it is done in a way that is socially and ethically acceptable.

Nicola Lacetera is Chief Scientist at the Behavioural Economics in Action Research institute (BEAR) at the Rotman School of Management and a Professor of Strategic Management in the Department of Management, University of Toronto Mississauga with a cross-appointment to the Rotman School. Mario Macis is a Professor of Economics at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School and Affiliate Faculty at the Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. This is an excerpt from their chapter in Behavioural Science in the Wild (Rotman-UTP Publishing, 2022.)

|

Share this article: