You have set out to equip business leaders to address mental health issues in the workplace. Why is this so important?

While any facet of life can impact our mental health, we spend 30 per cent of our waking hours at work — which means employers have a role to play in helping to address it. The business impact of mental health is also substantial: without mentally healthy workplaces, organizations risk reduced productivity, increased costs and loss of competitive advantage.

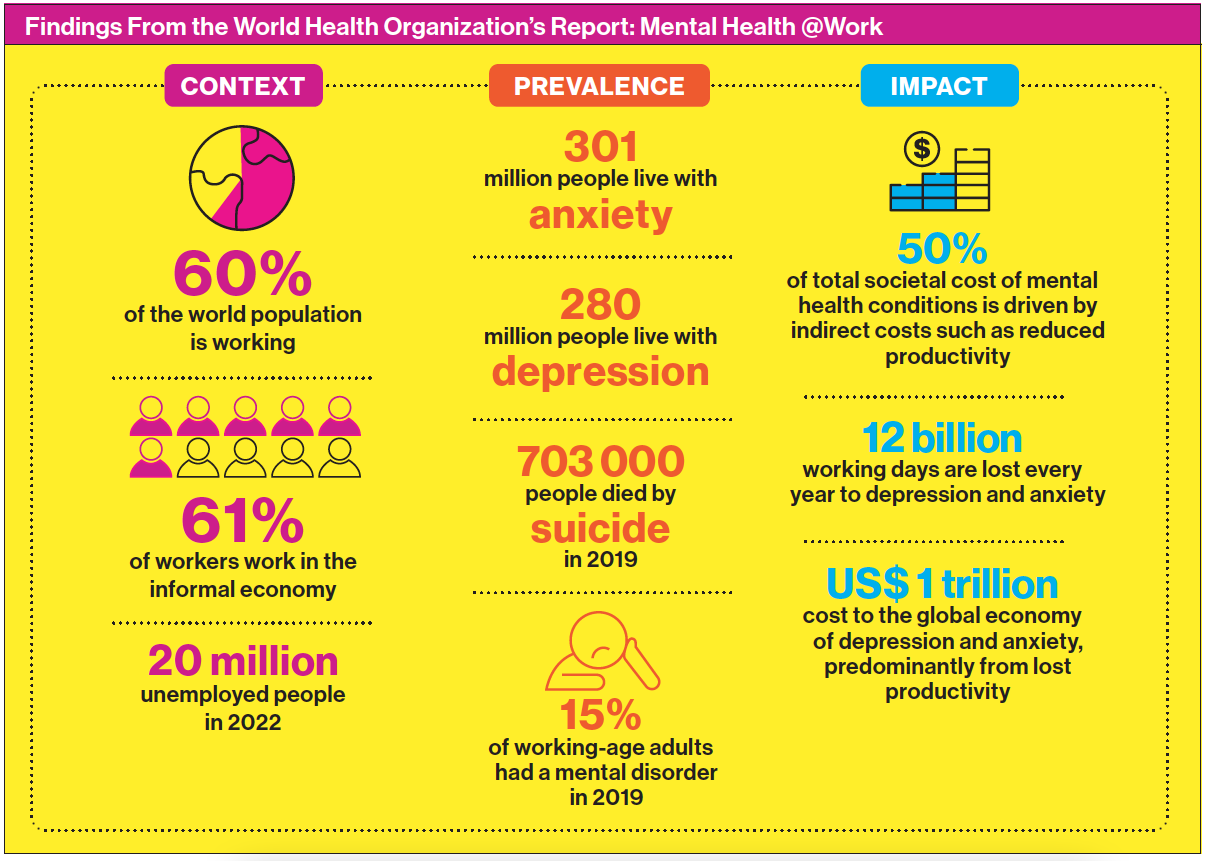

Work and mental health are closely intertwined, in that a safe and healthy working environment supports mental health while an unsafe or unhealthy environment can undermine it. If left unsupported, poor mental health can interfere with a person’s ability to work. The World Health Organization recently released a report that included recommendations to tackle risks to mental health such as heavy workloads, negative behaviours and other factors that can create distress at work. For the first time ever, it is now recommending manager training to build capacity to prevent stressful work environments and respond to workers in mental distress.

Global employers have a real opportunity to make a difference here, not only by tackling stigma and providing support when needed, but also by creating an environment where people can come to work and maintain their good mental health. For decades we thought about work as being completely separate from our personal lives. A degree of segmentation was normal. Then COVID-19 came along, and the boundary between work and life was completely blurred. But there is a silver lining here: We now have an opportunity to reimagine workplaces — and leadership — in a way that enhances people’s mental health.

Just how prevalent are mental health issues at the moment?

Globally, 15 per cent of working-age adults are living with a mental health disorder. These conditions are experienced in different ways by different people, with varying degrees of difficulty and distress. In the worst cases, the situation is dire: Globally, every 40 seconds someone dies by suicide. Without effective structures and support in place, despite a willingness to work, the impact of unsupported mental health conditions affects self-confidence, capacity to work, absenteeism — and the ability to gain employment in the first place.

According to a recent McKinsey Health Institute report [Addressing Employee Burnout, available online], today’s workers are reporting very high rates of burnout and distress. This report showed that while mental health exists along a continuum, the majority of employees are likely to experience some symptoms of poor mental health and well-being at some point during their working years. At the time of the survey, 59 per cent of workers reported at least one mental health challenge.

In recent years, the burgeoning mental health crisis has made it increasingly clear that we need systemic change to better support our minds. Here in the UK, and in many other places, demand greatly outweighs the supply: we’ve got young people on waiting lists to see a psychiatrist for up to two years; and referrals to our Crisis Mental Health Services increased by 86 per cent during the pandemic.

Before COVID-19, many people went to work in the dark and came home in the dark. There was no opportunity to pick the kids up from school, to attend the Christmas play or to be present at family dinners on a regular basis. The pandemic changed all of that for lots of people. The question is, How can we redesign work so that human flourishing is possible every day — not just on weekends and during holidays?

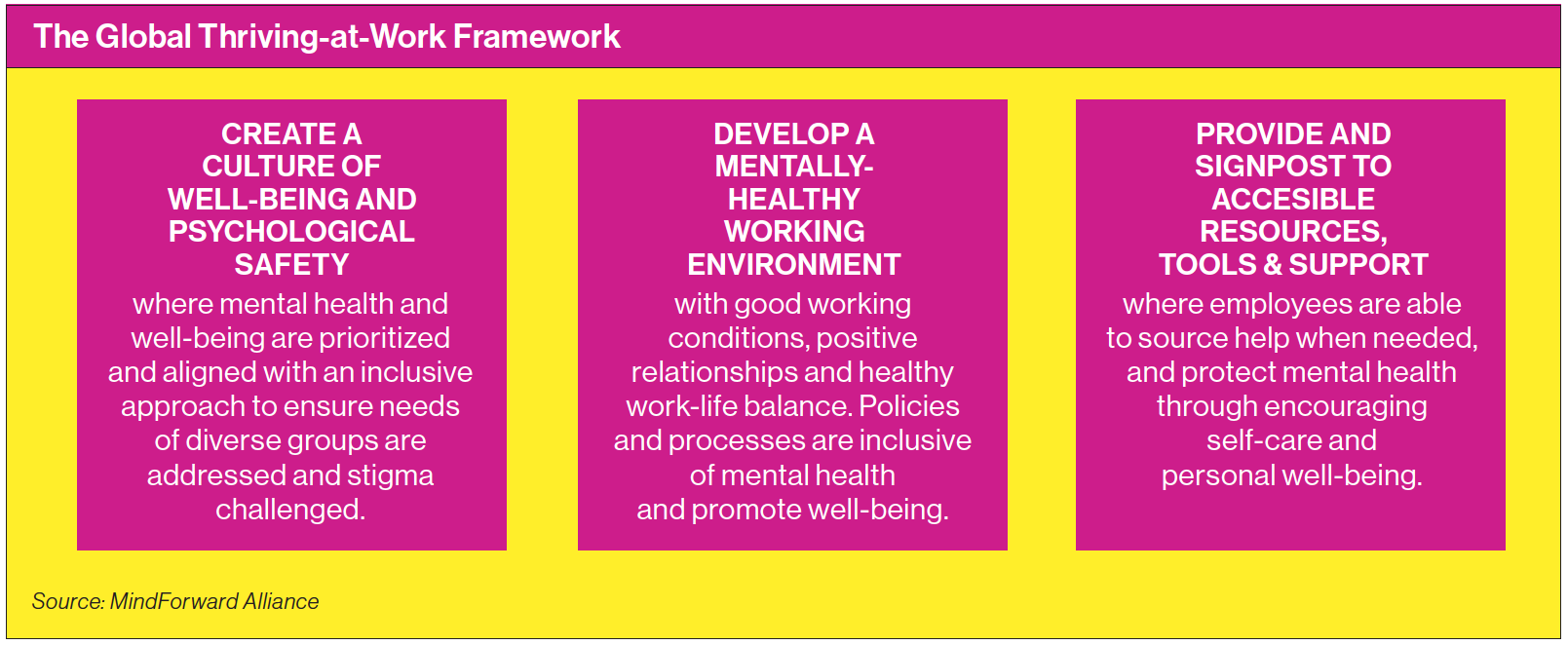

You have developed a framework to help organizations achieve this. Please summarize it.

Our Global Thriving at Work framework [available online] consists of three pillars. The first is to create a culture of well-being and psychological safety. This means proactively talking about mental health, creating campaigns and having leaders show their own vulnerability. For example, when a leader shares a story about a tough time in their life and what they did to overcome it, that can be extremely powerful. In big business there is this sense of bravado that you should never show a chink in your armour. But that is what I call toxic perfectionism. If leaders show up every day pretending nothing affects them, we are only going to perpetuate mental health struggles in organizations. I always advise leaders to be brave, not perfect.

The second pillar is to develop a mentally healthy working environment. We need to aim for an environment where everyone from junior staff up to the C-suite understands how to recognize early warning signs of mental ill-health — and knows how to have a conversation about it. The third pillar is to make resources, tools and support accessible. This includes recording and analyzing data around mental health. If you’re not recording absences or how people are feeling about their jobs at different points in time, how can you measure any of the changes you put in place? To complement our framework, we have a Global Thriving at Work Assessment [also available online] that enables businesses to measure their progress in achieving the framework standards and benchmark themselves against their peers.

Are there examples of companies that are already doing this, and best practices to follow?

Definitely. My colleagues and I are working closely with 79 global businesses around the world, including Microsoft, HSBC, BNY Mellon, Allen & Overy, PwC and Deloitte. Nobody has solved this yet, but these and other companies have put in an enormous amount of effort to create a mental health strategy. For example, HSBC is going to train all of its line managers in 66 countries on some basic mental health skills. At BNY Mellon, we’ve been training their employees around the world throughout the pandemic on how to have these conversations in different markets, incorporating cultural nuances. The list is long and there is some amazing work being done, but we are still in the early days.

For me, the ultimate goal is to make a difference for mental health globally. If we’ve got global companies like HSBC in 66 countries and Deloitte in 140, we can start to impact the entire world through the workplace. The other bit that excites me about the work we’re doing is around understanding what works in different cultures. For instance, talk therapy is a very Westernized model, and we already know that this approach doesn’t necessarily work in some places like India, where a family-therapy approach is more appropriate due to its multi-generational households.

Businesses are waking up to the fact that they must be part of solving the societal jigsaw puzzle. Health organizations will continue to do their bit, of course, but the private sector can accelerate the learning around mental health through experimentation and innovation.

You believe individual managers should be held accountable for the well-being of the people on their teams. How might this be achieved?

A number of companies we are working with have already started addressing this by expanding their 360-degree performance evaluations. They have added in data points related to mental health and well-being, so that entire teams are being asked whether they would feel able to talk to their line manager about their well-being, whether they were able to get support if they needed it, and whether the business is providing enough information and support around mental health. Then all of this is rolled up into a score that directly affects the manager’s performance appraisal. We’re seeing a similar thing being done for CEOs of businesses, as well. I can’t name the business, but one of our members is testing this out with their Global Chief Executive as part of efforts to create a culture that is healthy and inclusive.

You also believe mental well-being should be reflected in job design. What are some of the key elements to consider there?

That’s the next big challenge my colleagues and I are going to tackle. As we’ve been consulting with our 79 members, one thing virtually everyone has referred to is the punishing culture of long working hours. This seems to be accepted in just about all the businesses we’re working with — and not just accepted, but expected. When I was speaking to colleagues in India recently, they told me, “We have to stay up really late and continue working while the U.S. operations have their daytime hours.” Basically, they are being forced to mirror the time schedule in the West. Just imagine the impact that this is having on people’s sleep patterns — which correlate directly with mental health.

One thing I can say with certainty is that there is an appetite for change. We just don’t know exactly what it will look like. One element is, we need to stop creating jobs where people are paid enormous amounts of money with the expectation that they will only have a shelf-life of two or three years (because they will completely burn out). Instead, we should be creating jobs that have longevity and foster an environment where work is part of the employee’s well-being toolkit — rather than a place to come in and be punished for a few years, make lots of money, then move on.

The other thing is, people are living longer. Studies predict that most of Gen Z is going to have five careers because of how long they will live. Maintaining our physical and mental health for as long as possible — so that we build up reserves of stamina and energy — is not just good for people, it will be good for the economy and for communities. Jobs have to reflect that.

Research shows that certain preventative measures are highly effective in maintaining our positive mental health. Describe the Five Ways to Well-Being Framework.

Each individual’s well-being toolkit will be very personal to them, and we each need to figure it out. The framework I use is an evidence-based one from the UK’s National Health Service that has five elements: connecting, learning, giving, noticing and moving.

In my experience, connecting is the most important of the five, and actually, peer support is one of the best mental-health protection factors available. Your peer network doesn’t need to be huge to be strong. As long as you have dependable people to connect with on a regular basis, your mental health is going to be enhanced. Personally, I have a number of friends that I see for different things. With some, we talk about family issues; with others, work; and with others, we go for long walks. These connections are really important for me and foster a sense of belonging.

Learning might sound like an obvious element of well-being, but those of us who sit in front of laptops most of the day have something important in common: We need to learn to do something with our hands. I suggest learning something that actually avoids technology, like a martial art or playing a musical instrument, because it will use a different part of your brain and enhance your mental health in a whole new way.

Acts of giving and kindness, both big and small, improve our mental health by creating positive feelings and a sense of reward. You can achieve this in so many ways. It can be little things, like saying thank you to someone for something they have done for you; asking a friend or family member how they are doing — and really listening to their answer; or helping out in your community at a school, hospital or senior care home. All of these things will contribute to your feeling of purpose and self-worth.

The fourth element is noticing, which entails paying close attention to the present moment — to your thoughts and feelings, your body and the world around you. Some people meditate and others go for long walks without their phone. Whatever you do, it’s about being present and not being caught up in your head — learning to just breathe a little. And the final element is moving. We all know that exercise is good for us, but I’m not talking about running marathons. Even getting up from your desk every 90 minutes and walking around for a few minutes can be very therapeutic.

The key is to find your own version of ‘the five ways’ and practise them every day. It will be whatever makes you tick, but you need to be conscious about it — because if you can’t do this for yourself, you’re not going to be able to advocate for it in your team.

You have said leaders need to learn how to recognize the early warning signs of mental ill-health. What should they be looking out for?

Behaviour that is out of the ordinary or unexpected is usually a giveaway. For example, a star performer suddenly missing an important deadline or becoming very emotional in a meeting. Chances are, something is going on there. To make this a comfortable topic of discussion for your team, I suggest starting with yourself by identifying your own triggers and ‘stress signature’ — your physiological reaction to stress. The next time you’re having a bad day or week, write down what you’re feeling, what you’re thinking, and how this is being expressed physically. For me, I get headaches, I can’t sleep and I become very irritable and micro-managey. I’ve been known to send multiple e-mails about the same thing over and over to people, because I can’t trust that everything is on track.

Over the years I’ve built up a muscle so I can recognize my early warning signs — and I’ve communicated all of this very clearly to my team and to my friends and family. As a result, people can comfortably say to me, “Red flag, Poppy: This week you snapped at me three times!” or “You’ve already sent me three emails about this.” Then, we can have a constructive conversation because someone has held up a mirror — one that I myself have advocated for them to hold up.

This approach gives us permission to recognize each other’s stressors and start conversations in a factual way. The next time you see a warning sign, you can say, ‘This is the behaviour you’re presenting that is very different from your usual behaviour, so I’m just wondering, are you okay? Is there anything you’d like to talk about?’ That is how a mental health conversation starts. It can be that simple. In every organization and in every personal and family setting, we need to be talking about mental health as something we all have, just like we all have physical health. Let the conversations begin.

Poppy Jaman, OBE, is Global CEO of the MindForward Alliance. A global authority on workplace mental health, she is also a Director at Re=Balance and a Trustee for The Centre of Mental Health.

Share this article: