By Sandria Officer, PhD, Research Officer @JohnstonCentre

Worldwide focus on climate change, continuing disruptions from the pandemic, social movements, and demands for equity have forced companies from every corner of the globe to act on their environment, social, and governance (ESG) projects. The ESG acronym refers to the non-financial plans made by companies to measure their ecological footprint, equity, and social impact. It is known by:

- Environmental indicators: greenhouse gas emissions, waste generation, water security, and climate change risk strategy;

- Social indicators: employee and supplier diversity, data protection and privacy, community socioeconomic outcomes, pay equality, and worker health, safety, and human rights, and;

- Governance indicators: board independence and accountability; board oversight of executive performance and compensation; and board oversight of company strategy, risk management, performance, and disclosure.

The COVID-19 pandemic along with global focus on climate change magnified social problems inextricably linked to ESG issues. In the past two decades, ESG issues have impacted corporations’ profitability and long-term financial viability. The evolution of corporate asset allocation[1] began with ESG and has been driven by the universal ascent in consciousness of ESG. This change is seen by the increase in severe weather events, dangerous infrastructures, and troubling world economies. In addition, it includes the 2008 financial subprime crisis that shed light on the relevance of investor decisions and the centrality of their role, the progression in public awareness as it relates to social responsibility, and the significance of good governance practices.

The financial sector and many corporations in other industries amended their strategy and performance to reflect sustainable long-term value creation rather than short-term profit. Stock market and investor activity supported this trend with investment in intangible assets, often in sustainable new technologies. Intangibles are non-monetary assets that cannot be seen or measured but have risen in value compared to tangible assets like cash. For example, when U.S. capital markets surged at the end of 2020, technology companies with intangible assets that focused on issues such as intellectual property, brand reputation, and customer loyalty rebounded. Investors helped the sector recover by betting that the pandemic would boost ESG-related sustainable investments in e-commerce, cloud computing, and other technologies.

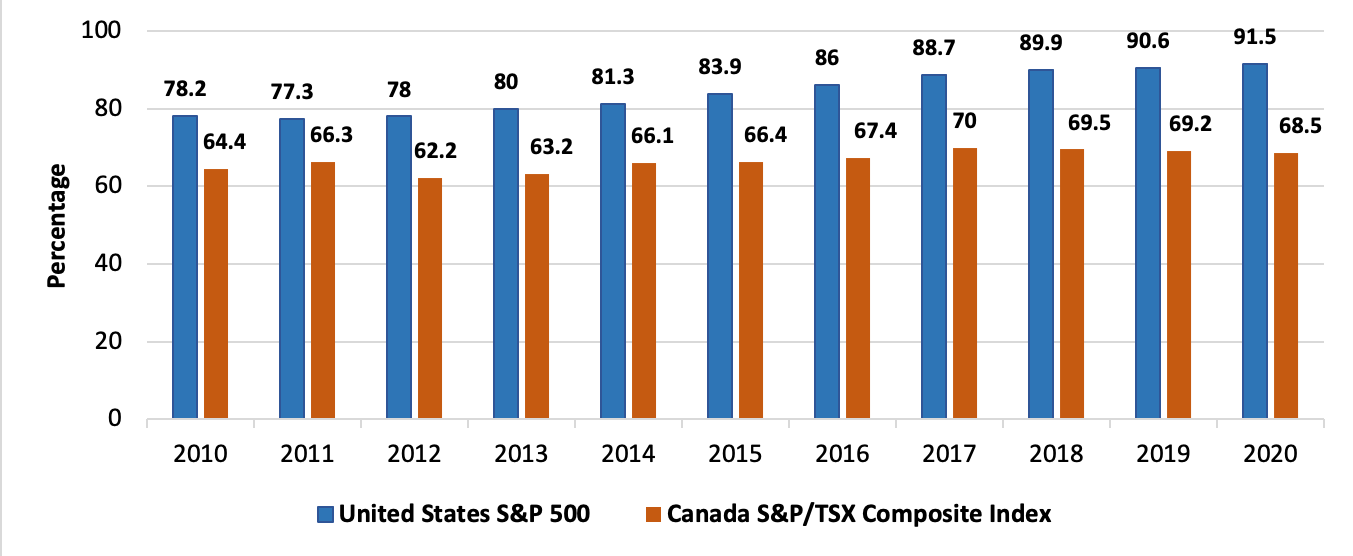

A recent report from the Royal Bank of Canada found intangible assets comprised the majority of enterprise value for most companies. As Figure 1 shows, nearly 70 per cent of Canada’s S&P/TSX Composite’s market value derived from intangibles, compared with more than 90 per cent of the United States’ S&P 500’s value in 2020.

Figure 1

Percentage of Intangible Asset Market Capitalization, Canada S&P/TSX Composite Index and United States S&P 500

Note: From: “Navigating 2021: 21 Charts for the Year Ahead” by Bloomberg and RBC Economics, December, 2020, p. 20 (https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/navigating-2021-21-charts-for-the-year-ahead/)

The report’s findings show Canada has lagged behind the U.S. in intangible assets and Canada’s intangible asset allocation has remained largely flat for over the past decade. In addition, it reveals that Canadian corporations need to invest more into research and technological development by building their intellectual property and by finding ways to retain it within a changing global economy focused on digital transformation and sustainable development.

The findings also suggest that investors are more willing to pay for companies with intangible values based on sustainability and goodwill rather than companies with just tangible assets found in real estate, buildings, or equipment. Investors and other stakeholders have shifted their expectations of companies from just financial market competitors to active contributors focused on the well-being of society and the environment.

Why are more companies issuing their ESG disclosures?

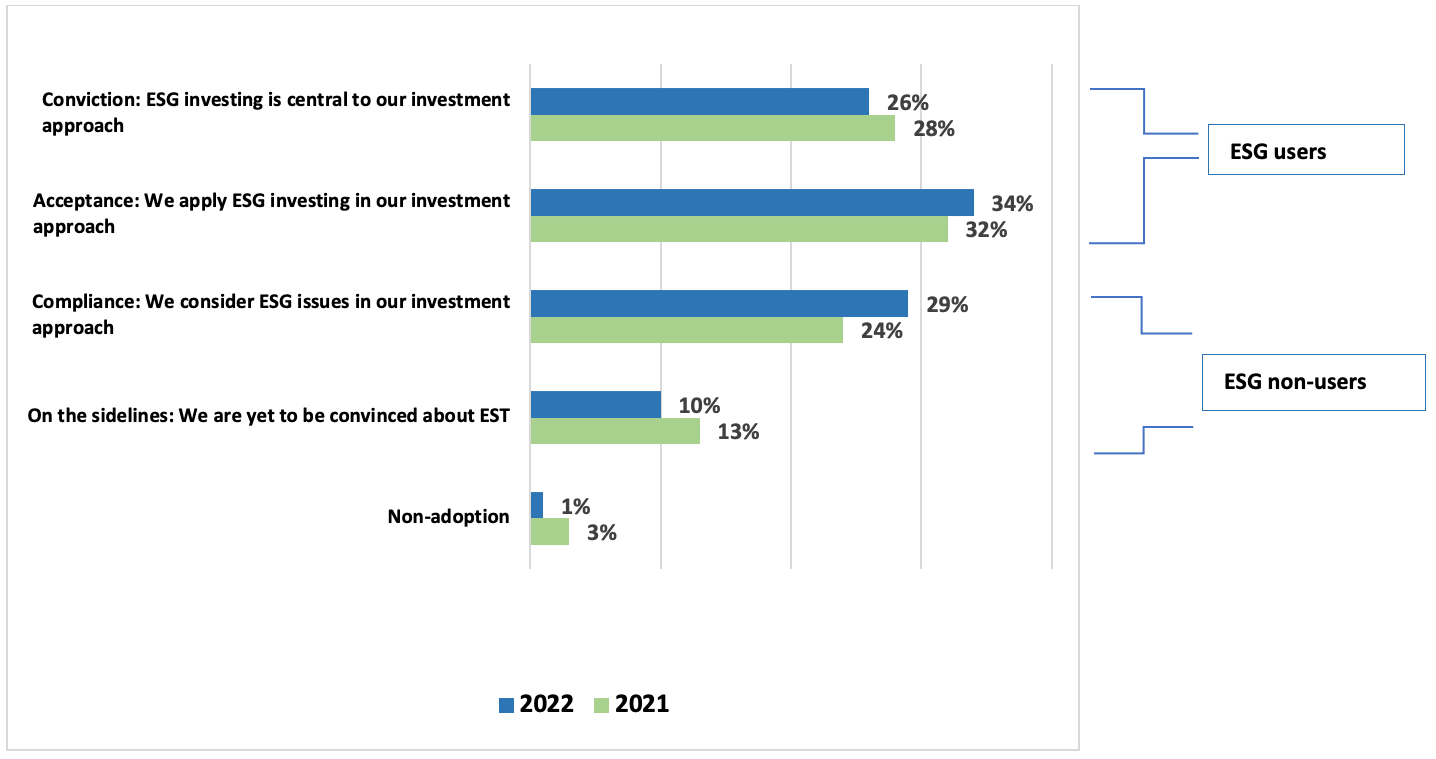

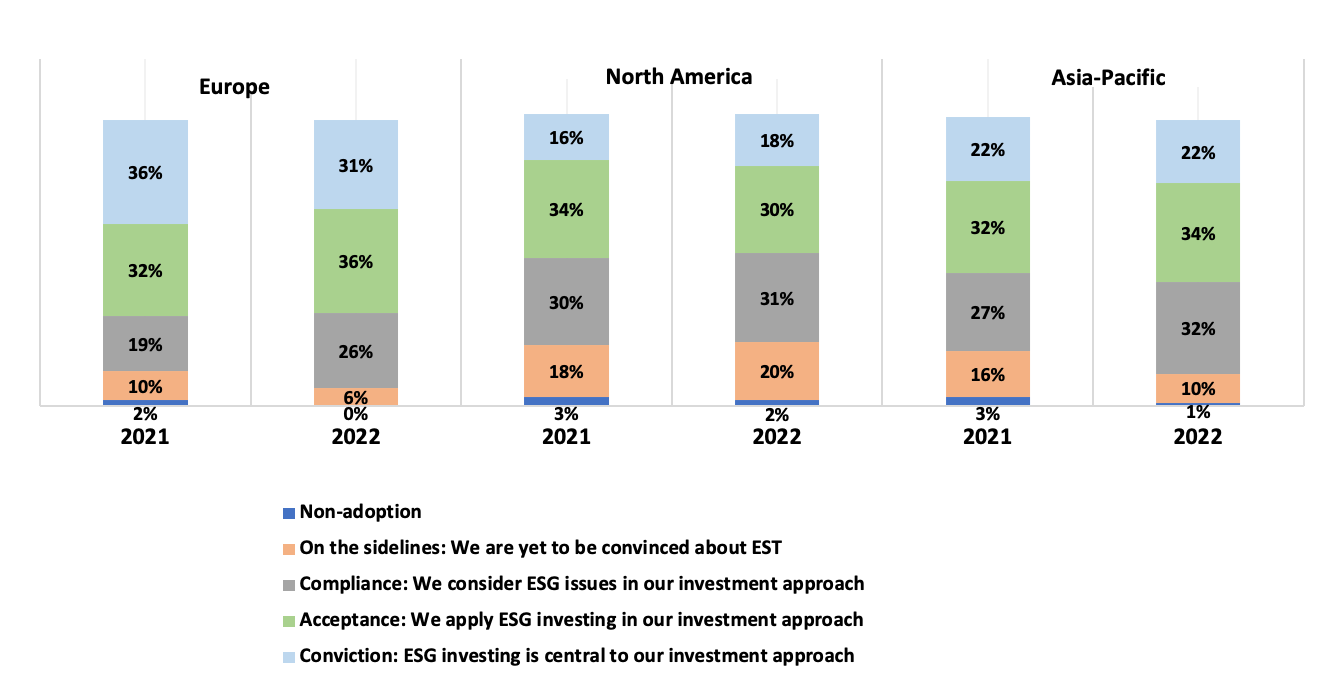

A growing number of companies are heavily burdened by investors, stakeholders, and broader societies’ demands for greater transparency in how they impact the environment, make social connections, and govern themselves. Many investors now make their financial decisions only after they obtain full understanding of a companies’ pledge to ESG. They realize that companies with good ESG metrics tend to outpace competitors. A 2022 global survey by Capital Group[2] found steady growth in the adoption of ESG by investors. As Figure 2 shows, in 2022, 26 per cent of investors say ESG is central in their investment decisions. This number is down slightly from 28 per cent respectively, in 2021. Figure 3 details Europe ahead of other continents with investors who say ESG is an integral factor in their reasons to invest (93 per cent Europe vs. 79 per cent North America, 88 per cent Asia-Pacific).

Figure 2

ESG Adoption Levels

Note: Which of the following statements best describes your organization’s overall stance on ESG investing? (Select on answer)

Data may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Figure 3

ESG Adoption Levels by Continent

Note: Which of the following statements best describes your organization’s overall stance on ESG investing? (Select on answer) Data may not equal 100% due to rounding.

As Figures 2 and 3 have shown, a growing number of companies have promptly issued their yearly performance reports on ESG in order to avoid environmental and corporate brand damage, and negative impact on financial earnings and potential future returns. The recent worry over companies shifting their focus from ESG to the financial market crisis has subsided as environmentally responsible companies have demonstrated that they are less exposed to systematic risks. According to research by Albuquerque, Koskinen, Yang, & Zhang (2020)[3], companies with high ESG ratings earned comparatively higher stock returns and experienced lower volatility than low-sustainability focused companies.

Sustainable ESG investing is forecast to exceed $41 trillion in 2022 and $50 trillion by 2025, which is 30 per cent of the projected total assets under global management, according to Bloomberg. While ESG disclosure reports consist of the three ESG metrics it can be observed that focus is mainly on the environment and social metrics and not on governance. The lack of focus on governance is not because governance is not important, rather it likely stems from the broad availability of governance information in other disclosure documents such as proxy statements. In addition, the environment is a global concern, which has a natural consequence of investors putting more focus on it than on governance information at this moment.

What are ESG rating agencies?

Increased calls by stakeholders for accurate information to assess corporate performance on ESG issues set off a new industry of ESG rating agencies[4] that provide companies with quantitative evaluations of their ESG data, ratings, and rankings. These agencies, faced with the growth in regulations and standards in the past few years, intensified their demands for more comparable and consistent ESG metrics from companies. The demands have led to regulators and other affected stakeholders supporting the move toward a global standard that encompasses frameworks, existing standards, and regulations to report ESG information.

ESG reporting now is done on a voluntary unregulated basis because the data is mainly nonfinancial information that is external to established auditor and regulatory oversight. Under these conditions, corporate executives have had the opportunity to take advantage of the ambiguity in the disclosure rules and overstate their sustainability records through greenwashing. Accordingly, ESG rating agencies disagree among themselves over the quality and credibility of the ESG reports that have been issued because they may contain biased information.

The disagreements among ESG agencies, however, undermine the reliability of their valuations and create capital market uncertainty. This points to the issue of whether ESG disclosure reports meet the informational needs of investors and affected stakeholders. Numerous stakeholders rely on corporate ESG disclosures to determine the amount of financial support they provide companies and under what conditions they receive it.

Individual ESG raters are in constant disagreement over a companies’ ESG performance, which is demonstrated in the raters’ distribution forecasts or in their credit rating differences. The ESG disclosure processes have become known for producing incomplete, inconsistent, and incomparable metrics. This disunity prevents a standard to develop that embraces the interrelatedness of ESG data, which capital markets and investors need. The inconsistencies in ESG ratings stem from these six common reasons:

1. Theoretical differences. For example, raters may have different beliefs about the idea of social responsibility;

2. Commensurability, which assesses the level of similarity that ESG raters obtain when they measure the same idea such as employee health and safety;

3. Differences in ESG raters’ perceptions of exceptional ESG performance;

4. Different ESG rater indicators (e.g., supplier performance and employee management) and different ESG rater weights (e.g., equal, back-test, industry-specific) that have been used, which can influence a companies’ financial performance outcomes;

5. Discrepancies in ESG rater data imputation methods that are used to replace missing data with substitute values. When the data gaps involve a variety of companies and times for different ESG metrics, big disputes occur among ESG raters with different gap methods. For example, the demise of the Lehman Brothers in 2008 marked the start of the global financial crisis and revealed the limitations of traditional measurement models on corporate performance and risk analysis. After 2008, the ESG rater agency industry began to consider ESG information as necessary in providing a better assessment of corporate performance, and in its place used a content analysis method. If ESG rating agencies compared different companies’ sustainability data in 2008 and in 2009, different methods would have been used in each year resulting in incomparable data, which would not have accurately reflected the issues being measured.

6. Benchmarking based on how corporate data providers define their corporate peer groups, which can be key in determining their performance. The lack of transparency among corporate data providers about peer group issues and observed rates for ESG metrics creates broad market inconsistencies and undermines their reliability.

Debate remains over the details of what standard global ESG disclosures might feature and include. The challenge stems from ESG’s broad scope that affects every business in some way, and its specificity in that ESG issues that companies face can differ vastly from within their industry, geographic location, culture, and life cycle, among other considerations. For these reasons, ESG standards do not exist to adequately address all of the ESG issues that concern all companies. In addition, the abrupt changes occurring in the ESG landscape have meant a minor issue can quickly switch into a major challenge that requires immediate redress such as required legal action.

Moreover, research[5] shows that there is a connection between corporate ESG disclosure and more ESG rater disputes when companies abide by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) advanced level reporting standards. Whereas companies in the environmental sector usually have reduced disagreements. To reduce market confusion and increased compliance costs in ESG reporting, global and Canadian monitoring and regulatory bodies have intervened in an attempt to unify ESG disclosure standards around the world.

In June 2022, the Independent Review Committee on Standard Setting (IRCSS) in Canada recommended the Canadian Sustainability Standards Board (CSSB) be set up and operational by April 2023 to manage ESG reporting amidst calls for better transparency and comparability of ESG data from companies. The CSSB arose alongside the global effort to standardize ESG reporting metrics, and as a result it works with the new International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB).

The ISSB launched in June 2021 to develop a global baseline for sustainability disclosure standards, and to help consolidate the plethora of existing standards. When the global standard is finalized, the CSSB will review it before they endorse it to ensure that the global standard is suitable for the Canadian economy’s high number of resource-extraction companies and small and medium size businesses.

Five strategic initiatives to execute now before the global standard on ESG disclosure takes effect

1. Expand your ESG disclosure strategy to address ESG materiality in your sector

Material ESG issues include the governance, environmental, or social issues that can impact the financial condition or operating performance of companies. Refer to the existing standards (e.g., SASB or GRI) for insight. For example, SASB will inform a company in the chemical industry (e.g., Dupont) that chemicals, water, and labour practices are among the material topics that need to be managed.

Critical stakeholders such as employees, investors, local community members, regulators, and the public should be consulted for their insights to identify business priorities that leaders may overlook. The company assessment and stakeholder assessment can be combined into a materiality matrix to prioritize topics that are important to stakeholders and companies, which can lead to a corporate competitive advantage.

2. Implement a strategic PESTLE & SWOT analysis through an ESG outlook

Use a sustainability-based PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technical, Legal, and Environmental) and SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) assessment.[6] The PESTLE analysis helps to better understand ESG trends linked to material issues. For example, some of the questions to consider might be: 1) What type of blockchain technologies for managing sustainable supply chains might help improve supply-chain resiliency and performance?; or, 2) What type of political regimes in supplier regions might affect supply volatility, ethical challenges, corporate reputation?

The SWOT analysis helps companies assess their current position in managing the material ESG issues that the PESTLE analysis identified, and it directs them to matters that need attention. For example, if the industry is oil and gas and you want to assess your rank, the SWOT analysis will identify the competitors who use micro refineries to transform waste oil into usable diesel fuel and the stragglers, among other issues.

3. Use key performance indicators (KPIs)

Key performance indicators (KPIs) are an integral part of the information companies need to assess company and activity-specific successes. Companies use KPIs to guide them in the right direction and also to divert their attention when needed.

For example, when product availability is a top challenge for companies in the retail and consumer sector, KPIs are used to assess the risks in the supply chain and the potential solutions. As most ESG disclosure reports and standards have process-based KPIs, companies can increase their competitive edge in the marketplace by developing outcome and impact-based KPIs, which they can later map onto their ESG reporting metrics.

4. Develop an ESG governance structure

Create an ESG committee that is cross-divisional focused on ESG best practices with access to the most recent news, technologies, and tools. The ESG committee works with other board committees (e.g., audit), human resources, and executive leadership across corporate divisions to build a sustainability culture into its ethic, which research has shown improves employee recruitment, retention, and productivity.

5. Track the return on sustainability investment (ROSI)

Companies that use the return on sustainability investment (ROSI) methodology link their sustainability strategies and financial performance to create stronger business cases for current and future sustainability initiatives.

Corporate leaders who monitor their companies’ intangible (e.g., employee engagement) and tangible (e.g., sales) financial returns that are tied to their sustainability strategy, enhance their decision-making, and build their competitive edge. The circular practice of developing benchmarks and tracking performance improves the analysis of forecasted return on investment (ROI) related to ESG-related capital investments and makes it easier to meet internal expenses.

The move towards a global baseline standard for ESG disclosures has accelerated in recent times. But companies that have built and implemented strategic sustainable operating procedures into their practices based on ESG standards have established a competitive advantage in the global marketplace. Oversight from their boards of directors ensures that companies’ ESG performance measures remain on track and profitable in the long-term.

Footnotes

[1] See Patrick Velte, “Institutional Ownership, Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance and Disclosure – A Review on Empirical Quantitative Research,” Problems and Perspectives in Management, Vol. 18, No. 3, (2020), 282-306.

[3] Rui Albuquerque, Yrjo Koskinen, Shuai Yang, & Chendi Zhang, “Resiliency of Environmental and Social Stocks: An Analysis of the Exogenous COVID-19 Market Crash,” The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3 (2020), 593-621.

[4] Dane M. Christensen, George Serafeim, Anywhere Sikochi, “Why is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of the Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings,” The Accounting Review, Vol. 97, No. 1 (January. 2022), 147-175.

[5] Michael D. Kimbrough, Xu (Frank) Wang, Sijing Wei, and Arui (Iris) Zhang, “Does Voluntary ESG Reporting Resolve Disagreement Among ESG Rating Agencies?,” European Accounting Review, Vol. ahead-of-print, (July, 2022), 1-33.

[6] Anastasia Christodoulou and Kevin Cullinane, “Identifying the Main Opportunities and Challenges from the Implementation of a Port Energy Management System: A SWOT/PESTLE Analysis,” Sustainability, Vol. 11, No. 21 (October 2019), 1-15.