You have observed a troubling tendency that often leads to the disruption of business models. Please describe it.

All too often, business strategies fail to effectively account for external change in the world. When faced with deep uncertainty, leadership teams tend to focus on recognized variables. This practice lures them into a false sense of security and results in a narrow framing of the future — making even the most successful organization vulnerable to disruptive forces that then appear to ‘come out of nowhere’. Futurists call these external factors ‘weak signals,’ and they are important indicators of change.

You have identified 11 such sources of external change that can sneak up on an organization. How did you go about assembling this list?

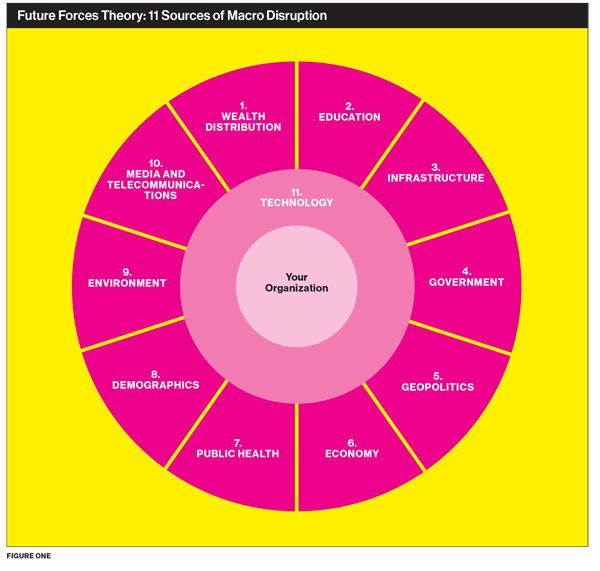

As a quantitative futurist, my job is to investigate the future, and that process is anchored by intentionally confronting internal and external uncertainties. I have developed a framework called Future Forces Theory, which shows that disruption usually stems from 11 influential sources of macro change. These sources broadly affect business, governing, and society. In 15 years of research, I have discovered that virtually all disruptive change emanates from one or more of these areas.

Paying attention to these external forces is more important than ever. Our world is now so interdependent that a change in, for example, geopolitics can have a significant downstream impact on media, telecommunications or public health. If you don’t connect what you are working on to forces of disruption in other areas, you can miss both the risks and opportunities on the horizon.

Some of the categories in your framework are less intuitive than others, like wealth distribution and infrastructure. How do these elements fit into the disruption landscape?

In recent months we have all been thinking about what the aftershocks of COVID-19 are going to be. Wealth distribution and infrastructure are two of the areas from which disruption is emanating during this pandemic, and this is starting to shift the future in different ways.

In virtually every country, the virus has highlighted fundamental equity issues related to digital infrastructure. I can’t think of a single place where people can say, ‘Our digital infrastructure is equally available to everyone.’ If you look at the future through this lens, some interesting signals are emerging. For one thing, in the U.S., many people have been driving to local libraries and schools to use the Internet, and these institutions have had to increase their bandwidth in order to meet the demand. It doesn’t get reported on, but we are seeing parking lots full of people without internet access.

This is an interesting trend because it is happening at the same time that the U.S. and other countries are figuring out what to do about 5G. Every day, decisions are being made about what the next generation of network infrastructure will look like, the role that Chinese technology

will play in it, and the sanctions and other geo-economic tools that the U.S. might use to convince other countries not to use Chinese technology. The access problem brought to light by the pandemic should have an impact on some of these decisions.

In terms of wealth distribution, vaccine implementation is going to be a big issue. As soon as a vaccine becomes available, there will be immediate questions around who gets access to it first. But we already have signals around this. In the U.S., the people with access to insurance have been able to elect to get tested for the virus. Already, access to testing is not distributed equally. The question is, what does all of this tell us about the future of society? Any time we look at the future of anything, it’s important to consider the 11 macro sources of disruption and look at the signals that currently exist within each — and to connect those back to the subject that you’re working on.

In virtually every country, the virus has highlighted fundamental equity issues related to digital infrastructure.

You actually believe it is possible for leaders to learn how to see the next potential disruption coming from a mile away. How can we learn to do this?

To be clear, none of this is alchemy or magic — but it does mean that no matter what industry you work in, you have to confront your cherished beliefs. One interesting example of our failure to ‘see around corners’ has to do with cars. Over 100 years ago, someone filed a patent for a flying car, and every decade since then, subsequent patents have been filed and prototypes have been built. Despite all of these efforts, the industry as a whole refused to confront its cherished beliefs about how cars work — which is why cars haven’t changed much at all since they were invented. And yet there is so much technology available and so many alternate ways to fuel cars.

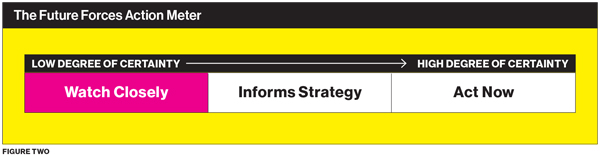

The way to see potential disruption before it strikes is to continually look for signals of change, categorize them as either weak or strong signals or trends, and then make sure that you have a system in place to make decisions based on that.

What do you say to readers who believe some of these categories could never affect their business?

One of the worst mistakes a leader can make is to think that any of the 11 sources are irrelevant to their organization. You have to be willing to create a constellation of signals, and really think through, ‘What are the next-order implications here?’ The key is to make a connection between each source of change and your company and ask questions like, ‘Which populations will be directly or indirectly affected by shifts in this area?’ ‘How might a shift in this area lead to shifts in other sectors?’ And ‘Who would benefit if an advancement in this source of change ends up causing harm?’

Take the newspaper industry. Twenty years ago a wide range of developments started happening in telecommunications. Suddenly there were early cellphones with cameras inside of them. Yes, they took grainy photos, but it was a camera inside a phone! There were also traditional digital cameras that had MP3 players built in. In the gaming world, haptic sensors were making it possible for users to get a sensory experience while playing a game; and in some parts of the world television was being broadcast over the air directly to a portable device.

If, as a media executive, you were to look at any of these signals individually, you might not have felt it told you anything about the future of newspapers. But taken together, these signals were incredibly important. Not a single news organization paid attention, and all these years later, virtually every one of them is now struggling.

This is a lot for any leadership team to monitor. What is the best way to create resources to take this on?

It’s really not that complicated. You don’t need to add headcount or set up a new department for the sole purpose of tracking signals. It’s just a matter of deciding that certain people within the organization are going to start paying attention to signals of change, and ensuring that there is some mechanism for sharing knowledge across departments.

Personally, I’m a big fan of cross-functional teams getting together regularly to do this type of work. My advice is to have a meeting once a week or once every two weeks for 20 minutes, and have everyone share the information about the signals they see surfacing. Use some tool to record that information. It can be as simple as a whiteboard where you write down all the signals and draw connections between them.

Now that we’re all socially distancing due to the pandemic, you can use a digital whiteboard. My colleagues and I use something called Miro, which is a whiteboard app that works on a desktop or mobile device. Every Monday we get together to share the things we’ve been paying attention to. We are constantly surfacing signals and trends for ourselves and on behalf of our clients. But as indicated, that’s not enough: You have to have some mechanism in place to tie those signals to your decision making and to map this information back to your business units.

One of the worst mistakes a leader can make is to think that any of the 11 sources of disruption is irrelevant to their organization.

You believe your framework can be used to broaden the expertise of both individuals and teams. How so?

The practice I just described is a great way to broaden a team’s expertise. There are 11 sources of disruption, so maybe you could get a team of 11 together, and each person takes on one area. From that point on, it is that individual’s job to monitor it. You can obviously take this up several notches and invite people to do active research in a rigorous way. There is a spectrum along which you can make this work.

It is also critical to ask, ‘In addition to these macro sources of disruption, what are the areas specific to our organization or industry that also deserve tracking?’ Then, again, get together with some regularity — maybe a couple of times a month — to share the signals you’re seeing, and

put them together in observing some kind of network information map.

On an individual level, one simple thing that anyone can do is to start actively reading. At whatever point in the day that you read industry reports or a newspaper, start doing that in a more active way, with the intention of looking for signals. I advise people to read one or two new things each day they you would not normally read. If you’re someone who mostly sticks to the business section of a website, seek out the arts section; or if you’re someone who focuses on finance, maybe spend some time looking at gaming. What are you seeing repeated, or what stands out to you or makes you think of something else? Write that down somewhere and actively make connections. This practice of active reading is another really great way to broaden your perspective.

When we work with companies on developing these capabilities, it’s amazing how quickly people start to build a capacity for seeing around corners. The bottom line is that willfully ignoring the signals emanating from these areas is a recipe for disaster. Keeping a watchful eye on the

future is a key responsibility for today’s leaders.

Amy Webb is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business, founder of the Future Today Institute and author of

The Big Nine: How The Tech Titans and Their Thinking Machines Could Warp Humanity (PublicAffairs/ Hachette 2019). She tweets

@amywebb.

This article appeared in the Winter 2021 issue. Published by the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, Rotman Management explores themes of interest to leaders, innovators and entrepreneurs.

Share this article: